On May 22, 1914, the bandleader, composer, and cosmic philosopher Sun Ra arrived on this planet in Birmingham, Alabama. One hundred and eleven years later, the State of Alabama and the City of Birmingham have officially declared May 22 Sun Ra Day.

Sun Ra — then still “Sonny” Blount — left Birmingham in January 1946 at the age of thirty-two. He would not return for many years. But that March he wrote back home with an update from his travels. J. B. “Jay” Sims — ebullient columnist for Birmingham’s Weekly Review, and a fellow musician himself — told his readers: “I know you will be interested to know that you have a card here from SONNY BLOUNT who has a hot five-piece combination playing in one of Nashville, Tennessee’s swankiest nite spots. And I know that Sonny is really sending the patrons with his famed Solovox.”

Before he left town, Sonny had been one of Birmingham’s hottest and most distinctive bandleaders, and that famed Solovox was one of the innovations that had set him apart. Introduced by the Hammond Organ Company in 1939, the Solovox was a small, electrified, amplified keyboard that could be attached to a piano to create a variety of sound effects: a forerunner to the modern synthesizer, it imitated the sounds of reed, brass, and stringed instruments and produced moody electronic vibes. Sonny took to it instantly. He introduced the Solovox to Birmingham audiences in late 1940, and he made it a central part of his act for several years to follow.

Birmingham musician and educator Frank Adams was a teenager when he joined Sonny Blount’s band in the early ’40s. I got to know “Doc” (as Adams became known late in life) many years later, and in 2012 we published his life story in a book titled Doc. “In his early years,” Doc told me of Sonny, “he had this thing called the Solovox. This was before the electric piano. It was an attachment onto his piano that made organ-type sounds, before the jazz organ was popular. It just attached, a little thing about the size of a cigar box, and you’d plug it in there and you’d hear these ghostly sounds—woo-oo, woo-oo. That was one of the things that got him this outer space business, because you’d hear this eerie sound coming through. It wasn’t amplified much, but he’d always attach it onto his piano.”

Indeed, Sonny was experimenting with electronic keyboard sounds long before they entered the mainstream of popular music; it would be years still before jazz, gospel, rock, and other musicians would follow his lead. And as Adams suggests, the “eerie,” unearthly hum of the Solovox—that woo-oo, woo-oo—fit perfectly into Sonny’s preoccupation with space, its sounds anticipating the sci-fi soundtracks of countless 1950s flying saucer movies.

Since I first began working with Doc, I’ve written a lot about Sun Ra’s Birmingham roots, both on this site and in my book Magic City: How the Birmingham Jazz Tradition Shaped the Sound of America. But lately I’ve been curious to know more about how Sonny’s Solovox experiments fit into the larger landscape of the Birmingham music scene. I wondered who else might have been drawn to the instrument in 1940s Birmingham, and how audiences might have responded. We can get some answers to these questions by digging into the local newspapers of the era.

The first newspaper references to the Solovox in Birmingham are music store advertisements. Pitching the new contraption to potential buyers. E. E. Forbes and Sons Piano Company first advertised the Solovox in August 1940, proclaiming “A NEW KIND OF MUSIC ON YOUR OWN PIANO.” For $190, musicians could add to their own pianos the “effects of ’cello, violin, trumpet, [and] saxophone.” What’s more, anyone could play it: “even a child can use the Solovox. It’s easily attached to any piano.” As the holidays approached, Forbes suggested the Solovox as a suitable Christmas present “for the entire family.”

We already know the Forbes store played an important role in Sun Ra’s development as a musician. In an era of rigid segregation, Forbes welcomed Black and white customers alike and gained a reputation in the local Black community as a kind of oasis from the widespread prejudice. In 1925, the Black-owned Birmingham Reporter singled out owner E. E. Forbes as “a man of great heart and sympathetic views. He is interested in humanity and is anxious about the progress of the Negro people.” The article commended Forbes’s store for the “fair treatment of its customers” and recognized Forbes’s salesman Harry Charles as the nation’s top seller of Brunswick label records. (Charles — a subject for another writing, another time — was also an important talent scout, who introduced to Brunswick and other labels a number of Alabama blues artists: Lucille Bogan, Cow Cow Davenport, Ed Bell, and Buddy Boy Hawkins were all “discovered,” championed, and/or recorded by Charles.)

As Frank Adams explained, Sonny Blount was a regular at Forbes, where (characteristically) he made a memorable impression. Noting the bandleader’s unusual diet, Frank Adams said: “He survived on grapefruit. He would go to Mr. Forbes’s music store, the biggest music store in town, and look through all the new music. He would probably be eating on a grapefruit, and he’d take his pen out and a piece of manuscript paper and copy the music. He’d stand there for maybe an hour, and drip grapefruit juice on the music and write it out by hand—he never would buy the music. People would be standing back, waiting to be waited on, and no, he wouldn’t move. Mr. Forbes would stand and watch him. When he finally got his music, he would say, ‘Thank you’ to the wall or something, and go on out. And everybody understood that.

“You would say, because it’s segregation and everything, ‘Why don’t they stop you from going in the store?’

“He’d say, ‘They like me.’

“‘Why would they like you, when you’re messing everything up?’

“‘They understand. That I’m a power. And really,’ he said, ‘we are friends.’

“He thought about white people that way. He said, ‘They are my brothers. They are my brothers, but some of them don’t know it yet.’”

Maybe Sonny never paid for the sheet music, but he must have saved up some cash to get his fingers on one of those new Solovoxes, almost as soon as they became available. The Solovox appealed to Sonny’s sense of novelty and to his already-established fascination with technology. Sonny was a collector of gadgets and new inventions, anything that could expand his musical universe. He had a transistor radio, with which he picked up the most modern sounds from New York City, and a wire recorder—with which he recorded those radio broadcasts, as well as live local shows by major touring artists like Duke Ellington.

And so, on December 20, 1940, Birmingham’s Weekly Review announced an “Xmas Night Dance” featuring “The Rythm [sic] Four With SONNY BLOUNT and His Electric Solovox.” Aside from Forbes ads promoting Solovoxes for sale, it’s the first reference I’ve found in Birmingham papers to the strange new instrument.

It is notable that Sonny found ways to incorporate the instrument into all of his many musical activities, including the Rhythm Four (his popular vocal quartet), the Society Troubadours, and his own Sonny Blount Orchestra. He played it at swanky dances for Birmingham’s Black and white communities, he played it for dances in the housing projects and at raucous floorshows on the outskirts of town, and he broadcast its sounds over the radio. Quickly, his Solovox created a buzz, further amplified by the local Black press. On January 3, the Birmingham World reported that “Tonight at eleven o’clock members of Birmingham’s ‘gilt-edge’ social set will be converging at the Elks Rest where the Esquire Club, popular young men’s organization, will be host at their annual dance. Music for the occasion will be furnished by the popular Society Troubadours’ Orchestra [with] vocal sallies by lovely Dolly Brown. Sonny Blount, pianist with the aggregation[,] will introduce his new instrumental solo rage which has captured the fancy of dance-goers hearing the novelty in private dance sessions.”

On the same newspaper page, the “Society Slants” column dropped the same mysterious bait: “The orchestra has planned to introduce a new instrumental treat and you had better be on hand” for what the paper called a “gyration special.”

The Weekly Review’s J. B. Sims would chronicle Sonny’s development on the instrument. “SONNY (BLOUNT) and his SOLOVOX, are getting better and better,” he wrote on January 17. For Sonny, this new toy was no passing fad: it was a core piece of his musical identity for the remainder of his years in Birmingham.

Other Birmingham musicians began to experiment with the Soloxov, too. Given the profound segregation of the city’s culture, it should be noted that Sonny Blount is the only Black Birmingham musician I’ve been able to identify with the instrument, while at least a few white musicians took it up. In mid-January, Edith Hagen — a Decatur, Alabama, music teacher and a representative for the Forbes store — added the Solovox to her broadcasts on Decatur radio station WMSL. Meanwhile, Forbes continued its advertising campaign in local newspapers, and by the summer Seals Piano Company had also begun promoting the device.

Advertisements for the Solovox suggest the target market for the new device. Drawings featured in Solovox ads exclusively picture women and girls, always white, at the keyboard. This is no surprise. Whiteness was the color of American advertising, and the piano was widely perceived as a feminine instrument, a parlor entertainment suggestive of domesticity and proper for girls’ study. Sammy Lowe, a fellow Birmingham musician and longtime member of the Erskine Hawkins Orchestra, noted in his unpublished memoir that, though his mother started all the Lowe children on piano, “at eight years old, I rejected the piano because at that time in Birmingham boys studying piano were called sissies” — a common trend in communities across the country. For Sun Ra, of course, conventions of gender, sexuality, race, region, or class (or any other human construction) were perpetually irrelevant.

By the summer of 1941, reports in the Atlanta Daily World reflected the growing reputation of both Sonny Blount and his trademark instrument. Of Sonny’s upcoming gig at Atlanta’s Sunset Casino, the Daily World predicted: “The famous Hammond organ will be worked overtime as Sonny, widely heralded for his lofty rank as an artist on the ‘solo-vax’ [sic], will be a singular treat.” Back in Birmingham, Sonny’s Rhythm Four was broadcasting five days a week on radio station WSGN. In August, in a rundown of the day’s radio highlights, the Birmingham Post-Herald noted that “The songs of the Rhythm Four continue to delight Birmingham audiences. Pianist Sonny Blount has recently added a solovox [sic] to his regular piano accompaniment.” The Birmingham News (in the racist language of the era) also noted the group’s unique lineup: “Four dusky boys, a guitar, piano and Solovox.”

Also that August, radio station WAPI introduced its own Solovox act. “Alabama on Parade” featured an “array of Magic City’s musical talent” and prominently featured Stanleigh Malotte on piano and Solovox (“a new instrument for rhythm-making”). Malotte was house organist both for WAPI and for Birmingham’s elegant Alabama Theater, where from 1937 to 1955 he presided over the Mighty Wurlitzer organ. Though Sonny’s Rhythm Four had very recently introduced the Solovox on WSGN, the Birmingham Post noted that “WAPI’s Alabama on Parade shows are also introducing for the first time on the air in Birmingham a new musical instrument called the solovox.” Maybe WAPI wasn’t exactly first, but the instrument was still enough of an unknown that some explanation was useful: “It is really an attachment for the piano, and when played makes the piano’s notes resemble the noteof the violin and various other orchestral instruments. One push button even renders a pipe organ effect.”

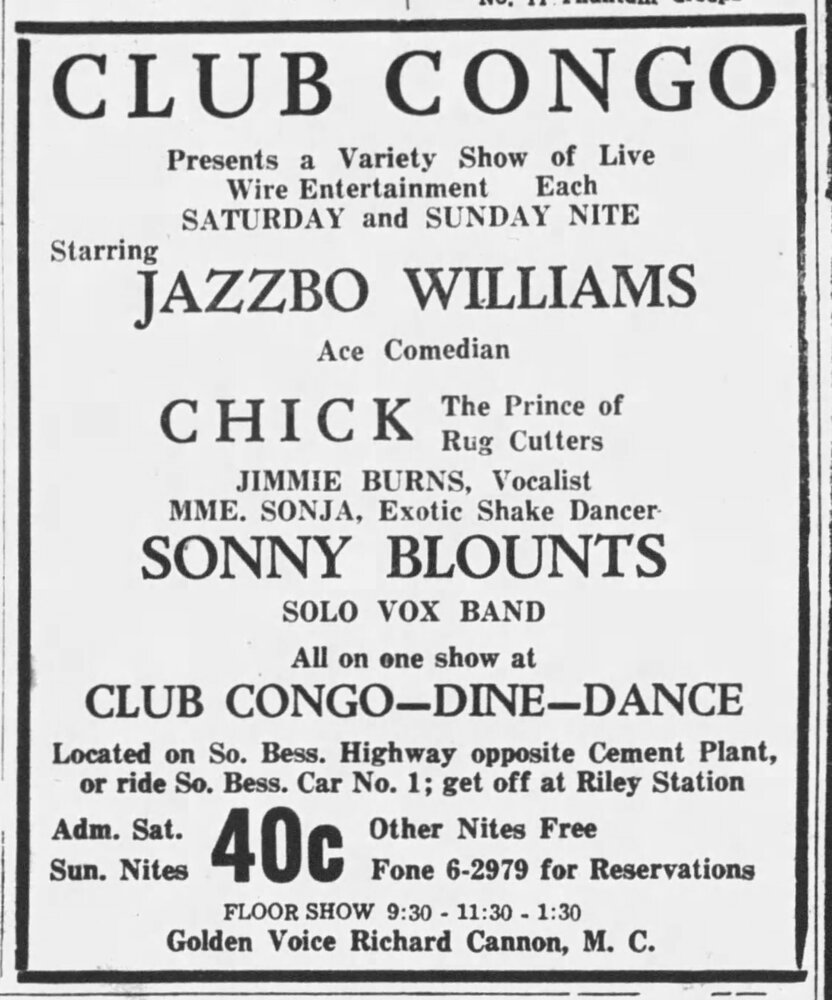

Still, Sonny Blount remained the Solovox’s most dedicated local player. Through the summer of 1942, “Sonny Blount’s Solo Vox Band” appeared every Saturday and Sunday night at the Club Congo, just outside of Birmingham on the Bessemer highway, in a “Variety Show of Live Wire Entertainment.” Two years later, Sonny and his Solovox were entertaining dancers weekly at Black Birmingham’s most prestigious dance spot, Fourth Avenue North’s Masonic Temple ballroom—and he’d added yet another novelty to the act. Offering “a tip to you dance lovers,” J. B. Sims advised: “Those MONDAY NIGHT DANCES at the MASONIC TEMPLE are really getting to be the real McCOY. And that SONNY BLOUNT certainly has some fine band to do the entertaining. He really ‘knock[s] you out’ with his Solovox and his very latest instrument, the Celeste” — another keyboard invention, similar to the glockenspiel, whose name derived from the angelic sound of its bell-like chimes. (Certainly the celestial connotation appealed to Sonny.)

The Solovox also found its way onto the dancefloors of white social spaces. In 1945, Jimmy Waldrop appeared on the Solovox as an “extra” feature alongside bandleader Ted Brooks’s Saturday night dances at the Thomas Jefferson Hotel. For the most part, though, the Solovox seemed to serve as a dinner party backdrop. Pianist Ed Nichols promoted his private services in the classified ads, promising to “MAKE YOUR PARTY A SUCCESS” with his piano and Solovox; he also provided “Dinner Music” at the new Jack O’Lantern dine-and-dance spot in the Birmingham suburb of Homewood, as well as at Harvey’s Restaurant on North 21st Street. Also performing on the Solovox at Harvey’s was Olga Riddle Dinken — “one of those rare musicians,” a columnist observed, “gifted to play any type of music, from the classics to swing.” And at the Little Southerner in Homewood, Gale Norman — “Hurricane of the Keyboard” and “Master of the Solo-Vox” — appeared nightly at the start of the 1950s.

By the late 1940s, however, the novelty of the Solovox had already begun to wear off: Solovoxes now began appearing with increasing frequency in Birmingham’s classified ads — in “good condition,” “like new,” or “perfect,” offered “At a bargain” or “Less than half price,” those Christmas presents of a few years past having lost some of their luster. (One seller, advertising a “HAMMOND SOLOVOX, practically new,” added this explanation for parting with the device: “Husband gone to Navy, must sacrifice my equity.”) The party pianist Ed Nichols continued providing Solovox backdrop for local diners, but through the 1950s and ‘60s almost the only newspaper references to the contraption appeared in the classified listings. By the 1970s the Solovox had even disappeared from the classifieds, made ancient history by the rise of the modern synthesizer.

As for Sonny, he settled after Birmingham in Chicago, and in 1948 he recorded himself — on another now-obscure technology, a paper tape recorder—playing the Solovox in his apartment. Here’s a sample.

For the rest of his time on earth, Sun Ra would adopt and experiment with any new keyboard technology he could find. In A Pure Solar World: Sun Ra and the Birth of Afrofuturism, author Paul Youngquist notes that “Sun Ra was an early player” not only of the Solovox and Celeste but of “the Clavioline, the Clavinet, the Kalamazoo K101, and the Rock-Si-Chord, among others, which he credited on his records with names such as ‘Solar Sound Organ’ or ‘Intergalactic Tone Instrument.’ He coaxed sounds out of them beyond the tolerances of their intended designs, taking the keyboards in strange new directions.” When Robert Moog introduced his first commercial synthesizers in the 1960s, Sun Ra was primed to embrace and extend their possibilities, expanding on the explorations he’d begun back in Birmingham, more than two decades before.

For this year’s (today’s!) Sun Ra Day, the city of Birmingham is host to multiple Sun Ra events, including two live performances by Sun Ra’s band, the Arkestra. Tonight (May 22, 2025), the Arkestra performs on the stage of the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame. Lee Shook, organizer of the week’s events, and Brian Teasley — owner of the Sun Ra-inspired music venue Saturn and a founding member of the band Man … or Astro-Man? — will present the Hall of Fame with an original Solovox for its permanent collections, a fitting nod to the cosmic bandleader’s early Magic City beginnings.

Very cool read, as was your book, “Magic City”. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much! Glad you enjoyed the book.

LikeLike

Thank You so Much for this email,so fascinating…I walked by Sun Ra’s home in Chicago today on 5414 S. Prairie (now a vacant lot); Sun Ra made home recordings there, some with the Solovox

Yahoo Mail: Search, Organize, Conquer

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi, Brad. Glad you enjoyed!

LikeLike

Gre

LikeLiked by 1 person