“Then, the way you always do, I met someone.”

This is how Billie Holiday tells it in Lady Sings the Blues, her 1956 memoir.

“He was a young boy, fresh up from the South—Alabama or Georgia. He played trumpet and his name was Joseph Luke Guy. He was new on the scene, just getting started as a musician. And he could be a big help to me.”

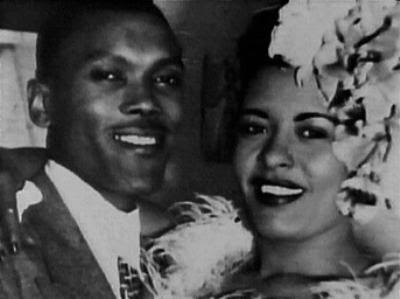

Joe Guy had come north to Harlem from Birmingham as a teenager, playing trumpet with the Rev. George Wilson Becton’s Gospel Feast Party, a jazz-fueled religious revival famous for its youthful band of “swinging apostles.” By the time he met Holiday he’d already been making his name as a forward-thinking, energetic jazz soloist. He was only five years Holiday’s junior, but the difference seemed greater: she was certainly more famous and was already wearier of the world. But Joe Guy was young and handsome and full of ideas, and his playing anticipated a new, modern era for jazz. He became Holiday’s trumpeter, her bandleader, her husband, and her drug runner.

Holiday and Guy met sometime in the early 1940s; a few years later, they were exchanging heartrending love letters from separate prison cells.

More on those letters in a minute. First, a little more about Guy.

Joe Guy appears in histories of jazz, when he appears at all, as a kind of footnote: at key moments in the music he pops up, horn in hand, then disappears. Dizzy Gillespie helped champion his career and borrowed from his playing. Miles Davis admired and learned from his solos. With Thelonious Monk and drummer Kenny Clarke, Guy belonged to the house band at Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem, the legendary nightspot whose late-night jam sessions laid down the groundwork for bop. You can hear Guy’s trumpet backing Coleman Hawkins on Hawkins’s seminal records, “Body and Soul” and “Stardust” and others; in his work with the Cootie Williams orchestra, you can hear him helping nudge the sound of swing into the future. He’s on Holiday’s records from 1945 and ’46, and for a while he led her touring band. The couple married, or said they did (they likely never got a license). And then he was gone.

Guy hasn’t fared well in the historical treatment of Holiday. In her biographies he’s often cast as villain, another bad man in a string of bad men, all more or less interchangeable. Ken Burns’s Jazz series narrates Holiday’s downfall in crisp prose and a portentous delivery, a series of short sentence-bursts suggesting a straightforward cause and effect. “In 1941,” the narration intones:

… she married a sometime marijuana dealer named Jimmy Monroe and began smoking opium.

Then she moved in with a good-looking trumpet player named Joe Guy.

He was addicted to heroin.

Soon she would be using it, too.

Really it’s not so cut and dry as that, and historians have quibbled over whose heroin habit came first. “He may have done things he shouldn’t,” Holiday herself once said to DownBeat magazine, “but I did them of my own accord too.… Joe didn’t make it any easier for me at times—but then I haven’t been any easy gal either.” One way or another, the couple was hooked, and their self destructions became wrapped up together. Under the influence, Guy’s playing became increasingly erratic, his reputation less and less reliable. Meanwhile, federal authorities were closing in on the couple. Jimmy Fletcher, a black narcotics agent, was assigned their case and closely monitored their movements (in the process he befriended, and very likely fell in love with, Holiday; what he considered his betrayal of her would haunt him for the rest of his life). The couple was creative in their evasion of the law, even recruiting into their service Holiday’s boxer, Mister. Fletcher later recalled that every day Joe Guy procured some new drugs from a connection in the city. Then he “walked the dog from way down on Morningside Drive up to 125th on Eighth and told the dog to go ahead. The dog would walk right in the Braddock Hotel … and the elevator operator was waiting for him.”

Mister would ride up the elevator, then walk down the hall to Billie’s door. Secured behind his collar was the day’s ounce of heroin.

Joe Guy gets half a chapter in my book, Doc, the life story of Alabama jazz man Frank “Doc” Adams, who played with Guy in the 1950s and very early ’60s. For my current book, a history of Birmingham jazz, I’m digging a little deeper into Guy’s story. And that brings me back to those letters.

In the spring of 1947, the feds finally caught up with Holiday and Guy, busting them for narcotics possession in their room in New York’s Hotel Grampion. Holiday was sentenced to a year and a day in the Federal Reformatory for Women in Alderson, West Virginia, while Guy awaited his own trial in a Pennsylvania prison cell. The couple sent letters back and forth from their cells; in recent years two of Holiday’s letters have surfaced and sold in auctions (they brought in around $6,000 apiece). The letters offer a poignant look into the heart of one of American music’s most beloved, most tragic figures—and they suggest a more tender and complex relationship than most biographers have allowed Holiday and Guy.

It’s a shame we don’t have more of the exchange—if any of Guy’s letters have survived, I haven’t seen them—but Holiday’s two surviving letters are compelling, aching documents. The first is dated July 6, 1947, and begins, “Joe Darling … I have read your letter so Many times, I know it by heart.” Friends are helping Joe get access to money and a lawyer, it seems, and Holiday frets that there’s nothing she can do, herself: “I Wish to God I could do anything to help you,” she writes, “but as you know both My hands are tied.” She worries, too, about her own career–“Maybe My public won’t forget me after all,” she hopes, “but a year and a day is a long time”–but she takes some comfort in news from New York that her friends and fans still ask about her and play her records on the airwaves. The letter continues (I’ve left the original punctuation, capitalization, and spelling as Holiday wrote them):

all this makes me happy but then it leaves Me Very sad all I think about is you My Work and Will I ever get straight and get started again in a Way I’m glad Mamas dead because this Would Just about killed her Darling there was a Mag that came out called Holiday My picture was in it I cut it out to send to you so you don’t forget What I look like (smirk) Bobbys sister Janey send a small picture of Mister so you Will be able to at least look at your family oh I Wish I had a picture of you please tell Bama [trumpeter Carl “Bama” Warwick] or Jimmy [Joe’s brother Jimmy Guy] or somebody to get one and send it to Me oh Joe Sweetheart you know I love you so it hurts you are all I ever think about please Write Me a long letter as soon as you can I can’t Write your Mother and Dad as I can only Write a few people But tell them I love them also and if they Write to me I Will answer I love you love you Will never stop

As Ever Your

Billie Holiday.

A few days later, in a letter dated July 12, she writes, just before bed: “I am going to try so hard to dream of you,” and quickly admonishes: “Don’t laugh. Sometimes I am lucky and can.” The prison had screened a movie that night, Sister Kenny with Rosalind Russell: “It was a very good picture but it made me kind of sad thinking about the last show we seen together odd man out” (James Mason’s 1947 noir, Odd Man Out). Lights out cuts Holiday’s writing short, but the next night she picks up her pencil again:

Well darling its night again. After I got thru my work today I just couldn’t write. I cried for the first time. Oh darling I love you so much I am so sorry you have to stay there in Phila. It must be awfully hot. Yes baby I gained nine pounds and I am getting biger all the time gee you wont love me fat (smile) But you must look wonderful. Youer so tall and you needed some weight. So thank heavens for that and what ever happens at your trial sweetheart keep your chin up don’t let nothing get you down. It won’t be long before were together agian. My lights has been out every since I last saw you. But they will go on agian for us all over the world. Write to me Joe as soon as you can. Ill always love you as ever your Lady Billie Holiday.

In her own trial, Holiday had blamed Joe for her addiction. When his trial came up in September, her testimony now exonerated him. The drugs had all been hers, she said—Guy didn’t even know where they came from. The jury deliberated for an hour, and Guy was released. “Billie Holiday’s Mate Freed,” the headlines read: “Word From Blues Singer Would Have Landed Joe Guy in Pen.” But Billie had spared him.

The next March, Holiday returned to New York—she was released two months early, for good behavior—but her prison time, and her unshakable habit, haunted her career. As a felon, she was forbidden by New York law to work anywhere liquor was sold, a restriction that cut her off from the night clubs and cabarets that were a jazz singer’s lifeblood. Almost immediately, she was using heroin again.

Joe Guy, meanwhile, was gone. According to the New York Amsterdam News, “The guys on the street intimated that … Guy, who was exonerated of dope charges, had recently taken an apartment in the 200 block of 129th St., but nobody could quite agree on the exact house.” As far as Holiday’s biographers are concerned, Joe Guy’s story ends there, with a vanishing act no one seemed too much to mourn. In the words of one writer, Guy “permanently dropped out of music” and “died in obscurity”; according to another, he “faded back down South where he was born.” For most historians, Guy simply disappears from the stream of history, his brilliant future—widely predicted, less than a decade before—evaporated.

Guy wound up back in his hometown of Birmingham, playing local clubs and mentoring younger players, who he emphatically urged to keep away from dope. Sometimes, friends and admirers said, his original brilliance still came through in his solos, and local musicians revered his playing. But his personal demons never left him alone.

Billie Holiday died in New York in 1959, at the age of 44. Guy died two years later in Birmingham. It had been more than a decade since the world had passed him by. He was 41 years old.

P. S. Earlier this week I announced a giveaway for my book Doc. (There are several good Joe Guy stories in it.) Thanks for all who entered the drawing by signing up to follow this blog, and congrats to phil-bond for the win. Hope you like it. Let me know.

Another P. S. What prompted me to write this post in the first place was a phone call, a few days ago, with Guy’s nephew Bernith, who lovingly recalls his uncle’s last days. I’m grateful for the added insight into Guy’s life, death, personality, and family, and I look forward to telling more of the story in the next book. Please stay tuned.

Meanwhile, here’s an interesting musical analysis of Guy’s career, including a complete, annotated discography.

You must be logged in to post a comment.