A couple of weeks ago I got my hands around this great little artifact: a drinking glass from Bob’s Savoy, for many years the beating heart of Birmingham’s Fourth Avenue North.

Under segregation, Fourth Avenue, between 15th and 18th Streets, was a thriving business and entertainment center for African Americans in the Magic City. It was home to restaurants, barbershops, beauty parlors, funeral parlors, hotels, poolrooms, and theaters, along with the offices of Birmingham’s most elite black professionals. The seven-story “Colored” Masonic Temple stood at the corner of Fourth and 17th Street, housing meeting spaces, hotel rooms, and a library, and hosting in its second-story ballroom a steady stream of swanky gala dances.

No place was more central to the scene than the Little Savoy Cafe, or Bob’s Savoy, located just across the street from the stately Masonic lodge. Its remarkable cast of characters ranged, through the years, from Sun Ra to Willie Mays, and its tables served as setting for impassioned political conversations that helped lay the groundwork for the city’s civil rights movement.

Bob was Bob Williams, one of Fourth Avenue’s most prominent and popular figures (“We know of no guy in town who has more honest-to-goodness friends than Bob,” remarked local columnist J. B. Sims in 1944). He cut an imposing figure, dressed in tuxedos and (often) a Shriner’s fez, cigar clamped almost permanently in his mouth. He was a tireless promoter of Birmingham’s black businesses and fraternal societies, an avid champion of local sports, a chief patron of the city’s distinctive jazz scene. Bob was a well-known advocate for African American rights in the city, a civic pioneer who condemned legal segregation and devoted himself with passion to black opportunity and community.

Bob’s Savoy sold chicken dinners, its specialty, for 35 cents; a bowl of beans or stew for 15 cents; and steak for 75. In a single year, reported Birmingham’s Weekly Review, Bob supplied his diners with more than four tons of chicken — not to mention all the other menu items or the constant flood of drinks. (“The atmosphere will soothe you. The drinks will groove you,” the ads ran; one customer claimed the Savoy sold more alcohol, in a given year, than any other Alabama business.) “Special cut rate meals” were available for students and office employees. And out of the back of the place a woman called “Messy Bessie” ran a sort of bootleg operation: “Anything you needed,” the musician Frank Adams laughed, whether strictly legal or not, “you could send for Messy Bessie and get it.”

*

In 1974, two decades after Bob’s shut its doors, an article in Black Enterprise magazine recalled that “Not all the black restaurants and nightspots of those years were as unpretentious and inexpensive as the Little Savoy, or as truly black.” Every year, Bob hosted more than one hundred banquets and meetings for any number of causes, hosting black business leaders and civil rights groups, along with an array of sports and entertainment celebrities. Visitors of all social classes found their way to the Little Savoy. A writer for the Chicago Defender marveled at the scene in 1943: “It’s the only place we have ever been into where people walk up to your table and say ‘We’ll give you six-bits or a dollar on your bill if you’ll save your table for us.'”

Hailing Bob’s as the “Largest Negro owned cafe” in Birmingham “and without doubt one of the finest in the nation,” another of the Defender‘s correspondents outlined the namesake restauranteur’s climb to fame. “Bob’s rise in the business world is almost like [a] fairy story,” writer David Kellum began. In 1932, Williams had arrived “penniless” from Chicago [other sources say New York]: he’d come South for an aunt’s funeral but stuck around. “For four years he worked for $10 a week at the Elks club, then one day an idea struck him. He had observed that the Negroes of Birmingham did not eat after 10 o’clock in the evening and so with a partner he opened the Little Savoy where he featured Southern fried chicken.”

That initial effort faltered, and Bob — whose connections stretched in all directions — appealed to “Chief of Police Brown, whose friendship he had acquired over a period of years. Brown paid his rent and gave him sufficient money [with] which to re-open his business.” (The specifics of that arrangement are not entirely clear, but other observers noted that Birmingham police ate free at the Savoy, anytime they wanted.)

“Bob’s business grew by leaps and bounds until his chicken bill alone averaged $1,000 a month,” Kellum continued. Today [in 1948] Bob’s Savoy does a gross business of $125,000 yearly.”

*

The Little Savoy served, too, as headquarters and hangout for the Birmingham Black Barons, the city’s Negro Leagues baseball team. The Black Barons conducted their business, celebrated their victories, mourned their losses, picked up their mail, and gathered for carpools at the Savoy. Williams made the cafe into an all-purpose hub for black Birmingham’s sports culture: he sponsored amateur basketball, football, and baseball teams and sold tickets for all the big games. He hosted packed-out after-parties for every local championship and promised local boxers free chicken dinners for scoring knock-outs in their first round. His place became hangout for every black celebrity athlete who lived in or came through town: Satchel Paige, Joe Louis, Willie Mays, Jackie Robinson.

And then there was the music.

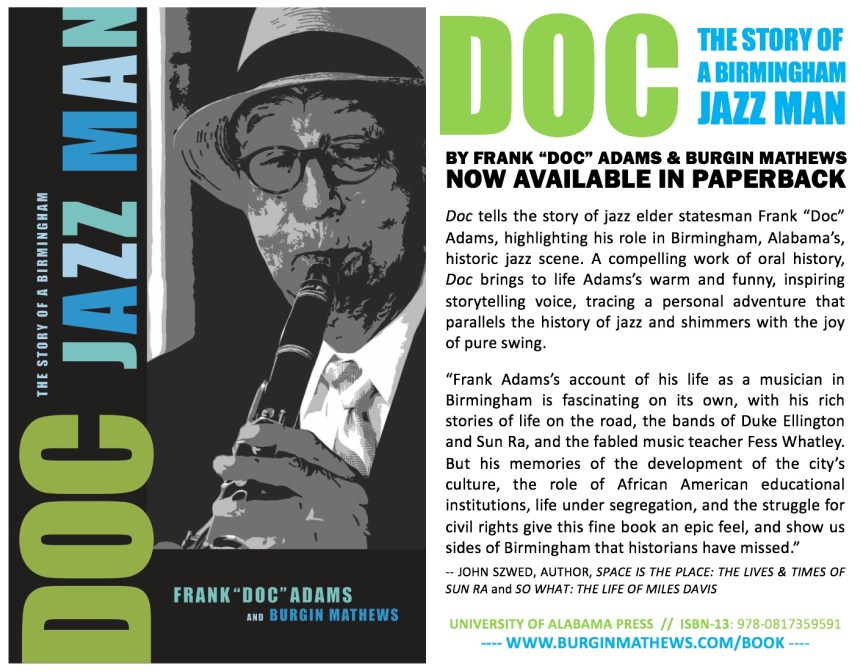

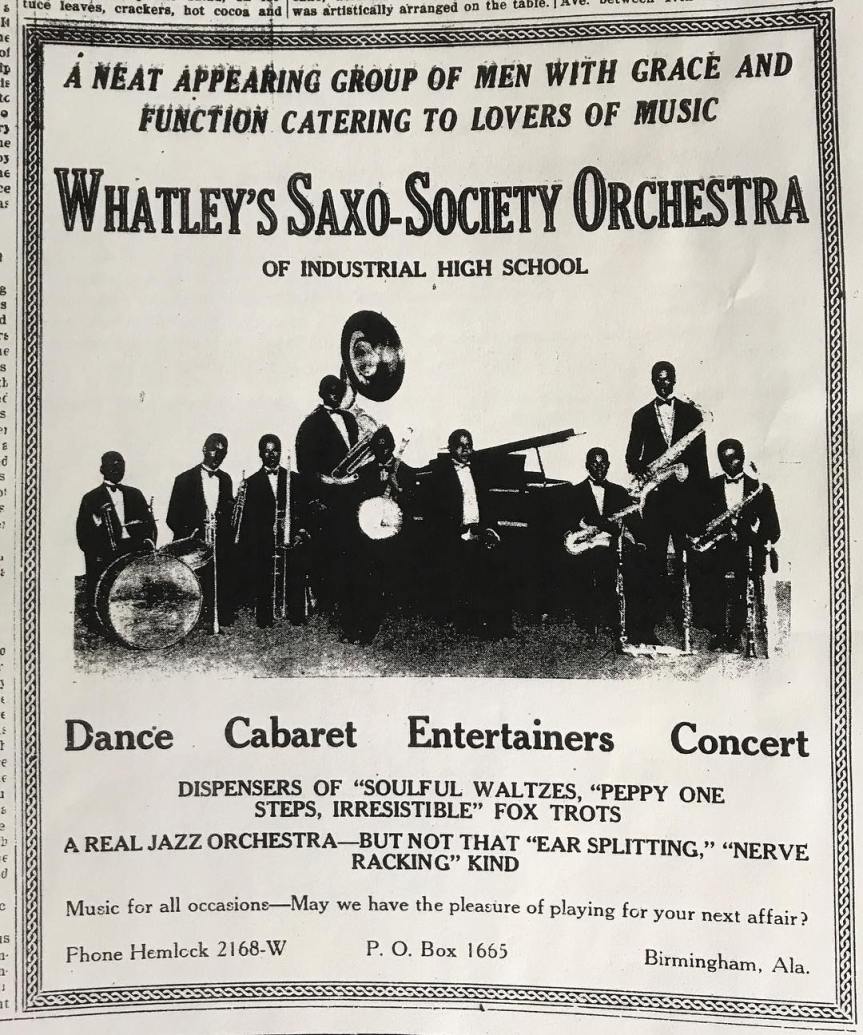

Frank Adams played at Bob’s as a teenager in the early 1940s, a member of Fess Whatley’s celebrated local band. In our 2012 book, Doc, Adams remembered: “Bob’s Savoy had international recognition. It was a huge place. They had beer and alcohol in there, and usually they would have a band. People would get off on Friday night, and they’d come in there — Friday, Saturday — they’d stay in there and drink beer and beer and beer. From all parts of Birmingham — Fairfield, Bessemer — they would come into town.

“See,” Adams continued, “this was the town. Fourth Avenue was just the heart of everything. You had all these barbershops; you had all the poolrooms and everything; and Bob’s Savoy was just the center. It was the centerpiece where everyone would go to be entertained. Any time at night, you’d see people crowding into Bob’s Savoy. Bob was a popular person and people always liked him. We would play in there sometimes in Professor Whatley’s band, and of course you couldn’t hear, because of the beer bottles and everything. But they always tried to have some kind of a band in there.”

Another band that played the Savoy was Sonny Blount’s group. In a few years, Sonny would leave Birmingham and become Sun Ra, one of jazz music’s most original, iconoclastic visionaries; in the early ’40s, he was an innovative, unpredictable favorite of Birmingham’s own homegrown jazz scene. In the summer of 1944, J. B. Sims’s column predicted big things for Sonny:

“One of the finest features I’ve ever seen exhibited in our town,” Sims wrote (a strong statement, coming from a popular ex-bandleader, himself, and a constant chronicler of the local scene) “was the very swelegant dinner given at BOB’S SAVOY last Monday night, by [promoter] J. B. BARKER on occasion of the first anniversary of the SONNY BLOUNT dance crew. We repeat, that we think that Sonny has one of the finest dance bands in the country and they should really go places. More power to ’em. . .”

National acts played the Savoy, too: Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Count Basie. Some nights they’d play the Masonic Temple across the street, then head to Bob’s and play a second show upstairs.

In the early 1950s, trumpeter George Washington was a budding musician in Frank Adams’s Lincoln School band room; today he’s a veteran musician of the longstanding Birmingham Heritage Band. In those early school days, he worked across the street from Bob’s Savoy at Brock’s Drug Store. “I must have been twelve or thirteen,” he told me in 2016. “I was the delivery fellow. And I rode a bicycle all over Birmingham delivering medicine. But because I worked at the store, they knew me around here, so I could go in the Savoy. I’d sneak in when the big bands come — like B.B. King, Louis Jordan — you know, I’d sneak in … until they catched me, and they put me out. Dr. Adams played round there. And that was, I mean — that was the spot.”

The Savoy catered to all classes, but within its walls social distinctions nonetheless prevailed. As historian John Klima observes, the Little Savoy was “in every way an exact replica of the caste system that existed within Birmingham’s black populace”: steel workers and coal miners crowded the first floor, while visiting celebrities, athletes, and the social elite gathered upstairs amid more upscale accommodations. On occasion, touring black bands performed at Bob’s to exclusively white audiences. Willie Patterson of the Black Barons described the arrangement to historian Chris Fullerton: on those nights, he said, “The whites had to go upstairs … the Negroes came downstairs.”

One Sunday in May of 1951, a fire ravaged the Little Savoy. Many believed the fire was a racially motivated attack: the next day, in nearby Fairfield, another fire broke out, and the homes of four hundred black families were laid to waste — while, in the words of the New York Amsterdam News, “a whole company of Birmingham firemen stood idly by, less than 200 yards away.” The fire department refused to help until they’d received word from their boss: police commissioner, fire chief, and “arrogant exponent of white supremacy,” Eugene “Bull” Connor. Word from Connor never came, and for four hours the firemen watched black homes burn. (“I don’t know nothin’ about it,” Connor spat at reporters, while the fire raged on.)

Whether or not the two fires — the one in Fairfield, and the one at Bob’s — were connected, no one ever determined. The Amsterdam News simply added that, in the last two years, “There have been 9 bombings of Negro homes” in Birmingham. Given the Savoy’s significance to the black community, it wasn’t a great stretch to suspect arson.

The Little Savoy suffered $25,000 in damages but rebuilt and quickly reopened.

*

In 1952, singer Del Thorne recorded for Nashville’s Excello record label a jumping little tribute to the Fourth Avenue scene. “Down South in Birmingham” was a musical postcard whose refrain exclaimed that “All the joints are jammed, down South in Birmingham.” Thorne encouraged outsiders to venture South, and she even gave a plug, specifically, to the Little Savoy:

Now, don’t go South and take the boys for fools,

‘Cause all of those cats have been to jive school

You just walk in and fall in line

And grab yourself a gal and have a good time

All the joints are jammed

All the joints are jammed

All the joints are jammed

Down South in Birmingham

Now, don’t get drunk, take everybody for your friend

‘Cause if you mess up that might be your end

Just drink enough to jump for joy

You’ll buy all kinds of drinks at Little Bob’s Savoy

The South, Thorne’s record proclaimed—and Birmingham in particular—was hipper than you’d think. At least, hip had its outposts there. Certainly, things could be worse:

When you get back, tell them the fun you had

The South ain’t the worst, and it’s not so bad

Every place you go, the joints were jammed

In the great Magic City called Birmingham

*

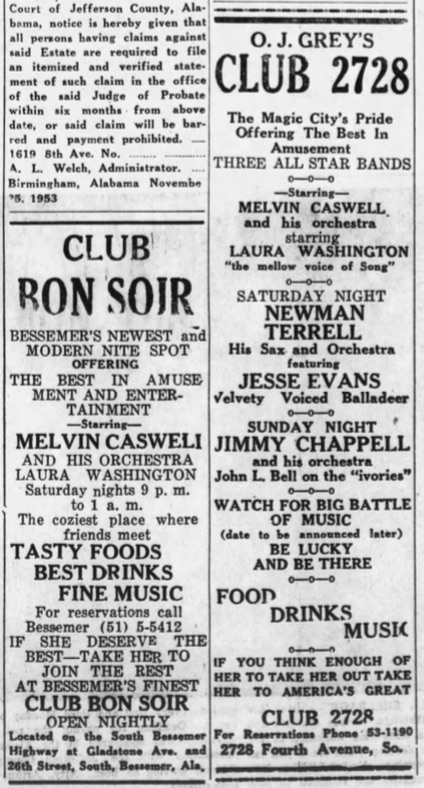

Another fire struck in 1958. This time, the Little Savoy closed its doors for good, and Bob moved on to other endeavors — in Detroit, in Philadelphia, and in Monrovia, Liberia, where he opened his own hotel. He exported to Liberia a piece of the Birmingham jazz scene, bringing with him in 1964 several local music stalwarts, including Newman Terrell, Melvin Caswell, and Walter Miller. All had been regulars at the old Savoy. Terrell and Caswell had belonged to Fess Whatley’s band before leading groups of their own. Before and after the Liberia gig, Walter Miller toured and recorded with Ray Charles — and he collaborated often, over the years, with Sun Ra, who he’d known since those first Birmingham days.

*

One more artifact: here’s an image from the J. L. Lowe collection of Birmingham jazz photos, housed in the archives of the Birmingham Public Library:

Left to right, that’s pianist John L. Bell, once known as “Birmingham’s Fats Waller”; Joe Guy, the great and tragic bebop trumpeter (he’d been both bandleader and lover to Billie Holiday and he played the house band, with Thelonious Monk, at the famous Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem); Chuck Clarke, a favorite local saxophonist and member of one of the city’s most prominent musical families; and drummer Cat Summerville. Summerville lived in the Masonic Temple’s fraternal hotel and played the burlesque shows upstairs in 18th Street’s Pythian lodge. Frank Adams remembered him as the city’s “champion drummer” and recalled that “He had a huge cat drawn on his drum”; George Washington also remembered, from his boyhood, Cat’s “huge, huge bass drum” and — on Cat’s head — the first conk, or chemically straightened hairstyle, he’d ever seen. In this photo, Cat’s drum skin features a drawing of Bob Williams’s Little Savoy.

*

I’m grateful to David from Manitou Supply Co. for spotting that glass from Bob’s somewhere in Pelham, Alabama, and thinking of me. He asked if “Bob’s Savoy” rang a bell, and I was thrilled to say it did. I’d scored a glass just like this several years ago on eBay, and I gave it to Doc Adams as a Christmas present. Ever since, I’d been hunting one for myself, even setting up a Google alert for Bob’s Savoy, hoping another would crop up for purchase.

No luck, until that message from David. So I’m happy, at last, to toast Bob Williams tonight from one of his very own glasses.

Bottoms up.

P. S. If you’ve got any personal or family stories (or memorabilia!) from Bob’s Savoy, let me know — I’m always on the lookout for more. And anybody know more about singer Del Thorne?

P. P. S. Sources for this history include multiple articles from the papers named above, as well as my many conversations with Frank “Doc” Adams. My interview with George Washington was conducted as part of the Alabama Folklife Association’s “Alabama Makers” project in 2016, with funding from the Alabama State Council on the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts. Any history of the Birmingham Black Barons baseball team (or its players) includes details of Bob’s Savoy: I consulted Alan Barra’s Rickwood Field and Mickey and Willie, as well as John Klima’s Willie’s Boys.

P. P. P. S. Ever since I wrote that book with Doc, I’ve been working on a fuller history of the Birmingham jazz scene, and this blog serves (among other things) as a place to share some of the outtakes and asides from the writing process. Some related posts include this birthday remembrance of Doc Adams, one of my early interviews with Doc, and this excerpt from our book together. There are brief biographies of bandleader and singer Ethel Harper (parts one and two), bebop trumpeter Joe Guy, and saxophone screamer Lynn Hope, plus a variety of Sun Ra-related resources. (Stay tuned, in the next few weeks, for some more cool Sun Ra stuff.) There are rare photos from Birmingham’s jazz history, links to more(!) photos, and a little Fess Whatley-inspired art. There’s a short write-up on 1963’s star-studded “Salute to Freedom” civil rights concert in Birmingham. And there are glimpses into the writing process itself: an old table of contents, a moment of despair, an occasional breakthrough. Some stories just don’t fit the book’s design as it evolves, and creating a space for them here allows me to let them go; on other occasions the blog becomes an excuse to think through some cluster of details that I just don’t know what to do with. Sometimes I just come here looking for help (what can you tell me or show me, that I might not already know, about Bob Williams and his Little Savoy? Or, again, that Del Thorne record?)

At any rate, thanks for coming along.

Oh / and / also — in the latest issue of the journal Southern Cultures, there’s an article I wrote about all this Birmingham jazz. Check it out, stay tuned, and thanks.

You must be logged in to post a comment.