Today, an excerpt from my book Doc – and a chance to win a copy of the book’s new paperback edition. To win, submit your email address on this page to follow this blog. This Friday (4/26), I’ll put the new followers’ names into some kind of hat and randomly draw a winner. (If you’re impatient – or read this after Friday – feel free to go ahead and buy yourself a copy here or wherever else you buy your books.)

Doc tells the story of Frank “Doc” Adams (1928-2014), a beloved icon of Birmingham, Alabama’s historic jazz scene. In the early 1940s, the teenaged Adams belonged to Sonny Blount’s band, which was already pushing the bounds of local convention; a few years later, Blount would move to Chicago, become Sun Ra, and launch his Intergalactic Arkestra, creating a new kind of music for the cosmos. Adams joined Blount’s band after a brief fallout with Fess Whatley, leader of Birmingham’s preeminent dance orchestra, but after patching things up with Fess, he found himself playing in both bands. Whatley led the music program at Industrial High School, where Adams was a student, and he was notorious for his strict discipline and rigid approach to music. In Sonny Blount’s band, meanwhile, it was another culture entirely.

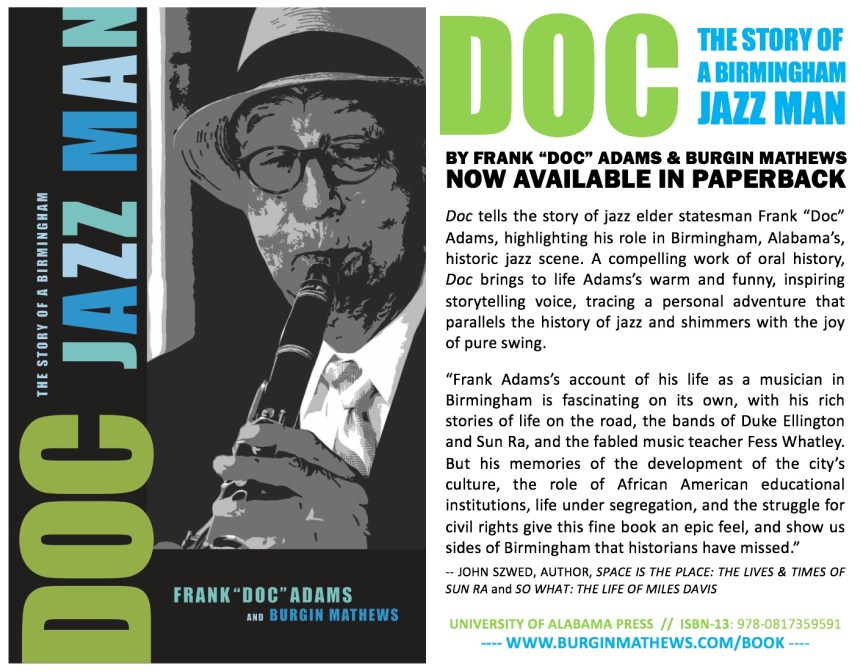

Doc: The Story of a Birmingham Jazz Man is a work of oral history, drawn from two years of weekly interviews with Frank Adams. Even into his 80s, Adams was a consummate musician, teacher, and storyteller, and his memories of Sun Ra represent the only detailed firsthand accounts of that musician’s early years in Alabama’s “Magic City.” The following excerpt comes from Chapter Five, “Outer Space.”

… Blount’s band was real unique. Everybody in there couldn’t read music real well, but he could put them together: I admire Sonny for being able to mold his musicians together to do things that he did. His orchestra would consist of maybe three trombones or five, it didn’t make any difference — he wanted to know how you sounded and how you sounded. If two bass players showed up, they were both on the job: he’d have two. Some of the musicians might have complained, because they’d have to split the money more ways, but Sonny wanted to hear what each one of them could do: how it all sounded together.

As I said, he lived in this rickety old house, and his whole world was in that place. It was a wooden frame building. As far as we got, and anybody got, was the front room, and that was where he had his bed and where he rehearsed. I think he took his meals in there. We understand that he had a sister or somebody, but nobody ever saw anybody there in the house. He would always be there, and he had these records stacked about five feet off the ground, these 78 records, and he had his piano in there. I remember that the hallway was about to fall in — you could step down in a hole or something if you weren’t careful — and the furniture was in shoddy shape.

Always it was very crowded. Whenever we had a singer, after he set the drums up, the singer would have to be out in the hallway, and he would call that person in whenever they would do a vocal number. The saxophones would be up against the wall over here, and the trumpets would be somewhere back in there. But you didn’t think about it. There was never any talk about anything but the music. He had a wire tape recorder, and he had a shortwave radio — I don’t know how he got it — and he could get music out of New York, like from the Savoy. He would have all these wild players on there, like Don Stovall. They were playing bop before bop was even heard about. He’d listen at night to that, and he’d play that back for you. It was the craziest music, but he would say, “That man’s not crazy. You just aren’t able to understand it yet. He’s trying to tell you something, but you don’t know what to do. He’s just trying to tell you he’s free — okay? So listen at it.” And if you listened long enough, you’d get it.

He would say, “I was born with x-ray ears; I can hear all these things you humans can’t hear yet.”

He had people like Henry “Red” Allen on that transistor radio, and they would be playing the trumpets: they would be playing very differently than you would hear them play in a concert, in a ballroom, or even on a record. It was a wild thing, and they would be playing number after number after number.

Sometimes if there was a big band like Jimmy Lunceford or Benny Goodman, he would transcribe that off the radio; he’d copy his arrangements right off the radio. If a band would come to the Masonic Temple, I don’t care who it was — Duke Ellington — he’d put that little wire recorder down there, and in about two or three days, he’d have all those parts written down, by hand. Nobody knew how he could do that.

Of course, Professor Whatley called me back after reflecting on what he had done. So it wasn’t but a couple of weeks before I was playing with both Fess Whatley and Sun Ra. That gave me two bands — and there was a great difference between Fess Whatley’s band and this Sun Ra experience. I know that sometimes I would look at Whatley’s music, and I would compare it to Sun Ra’s. If a vocalist would be singing, Sonny’s background music would be much simpler to play, lots of whole notes and things. Professor Whatley would have bought and copied out arrangements that would have these cascading runs like the pros would play. On the “Swanee River,” you’d have maybe a sixteen-bar reed chorus — Sun Ra didn’t have that type of thing, but he’d play a lot of blues. He had a fellow named Teddy Smith who played saxophone — a natural. They would play this “Hootie Blues” that would go fifteen minutes. Teddy Smith would be out there playing, playing, swaying from side to side; the people would be hot and sweaty and perspiring, and he’d go on and on and on.

Sonny was very popular because he had these soloists, and if you got out in one of those public housing projects where he played, your three-minute record wouldn’t do. If you played Glenn Miller’s “In the Mood” and had to stop after three minutes, like the record — those folks want to stay out there eight minutes, perspiring. That’s what they call dancing. Even a blues band like B. B. King: they could play what they recorded, but that’s not enough for dancers. They want to get out there and dance until they fall out. So you had these soloists who could carry on all night. That was one of the things that made Sonny’s band so popular in certain areas: Sonny could play the thing through once, twice, over again, and add something to it — and people liked that.

Now, Professor Whatley’s band: he’d play a dance, and we’d play a number — maybe “Tea for Two” — and then the number would be over, and people would sit down. When I left Birmingham, I found out that people don’t do it that way in New York and other places: you play sets of numbers. You’d have a set of four or five numbers before people would sit down. Sonny would take just one number, and play it for thirty minutes if he wanted to, as long as he saw people out there dancing.

Of course, Professor Whatley believed in the strictest interpretation of things. Sun Ra would take liberties — and he was composing his music, so he had a say-so in it. Sun Ra took pride in who he was as a creator of music. And that was all he did; morning and night, it was music. He’d say, “I can’t afford to be sick, because my music demands that I’m working twenty-four hours a day on it.” Said, “I wish I didn’t have to do that, but — it’s my mission. And even if I am sick, I’m still creating.”

So Sun Ra was in demand, because his band could improvise. They could start from the back and go to the top, and all that type of thing. And they had some showmanship — they could move a little bit. In Whatley’s band, you just stood there; he didn’t want you to move. Whatley had all these rules, that if you were playing a wedding or something, the band was not to eat the food — because, he said, “You’re the servants.” But in Sun Ra’s band, during intermission, if there was some food out there, they were going to get it. And with the people they were playing for, it was okay.

Man, Sun Ra: that was jazz music. Those guys didn’t wear tuxedos, they wore what they could. He didn’t tell you certain things to wear, like all the other bands would, and as a consequence, they said he never got those jobs over at Mountain Brook Country Club — because his band would be in their BVDs or whatever. Somebody might have a tux on, but the next guy might have his T-shirt on. And Sun Ra wouldn’t discuss that. It was all okay.

He played all over the housing projects — on the street, anywhere he could play. And when I finally started playing with him, that was a change in my life. I found out there was a discipline in Sun Ra’s band that you wouldn’t necessarily perceive. Whatley’s thing was this rigid discipline, which was okay, but in Sun Ra’s band, he had his own concept. With Whatley we were strictly doing what was proper. The dynamics wouldn’t be changed; you weren’t allowed to get up and play a solo unless it was written down. But with Blount, you could stumble over something, and then go back and try it again. And it was the sort of thing where you could talk to each other; you could have fun. You would sit there sometimes all night. If somebody was making a mistake, you could stop and help him — there isn’t anybody getting mad about it.

Sun Ra had discipline, but he had a thing where you would want to discipline yourself. If you messed up, he might say a little something and just pinch you with the fact that you should know better than that: you’re disrespecting the music. He wouldn’t talk about it so much, but you know; you know you didn’t play your best.

When I was playing with Whatley’s orchestra, it was mathematical, precise — and I marveled at that. Everything Fess Whatley did had its place: when to get up, when to go to bed, what to read. I would organize my thing, and it was good.

But I knew there was something else out there in this jazz music.

*

That’s all for now. For more, check out the book Doc. Sign up to follow this blog, and I’ll enter you in a chance to win a copy this week; I’ll announce the winner this Friday, and post a new story about another of Birmingham’s jazz pioneers, the bebop trumpeter Joe Guy.

You must be logged in to post a comment.