Okay, friends and strangers, I could use your feedback.

Here’s a short, working synopsis of my book in progress. I invite your input (on content, style, or any nitpicking details) in the comment section below. To chime in, you need zero prior knowledge of the subject matter, just an honest gut reaction. I’d like to know what works for you here and what doesn’t, and what could work better—anything you think might better persuade a person to pick up and read this book.

Thanks for taking a look.

*

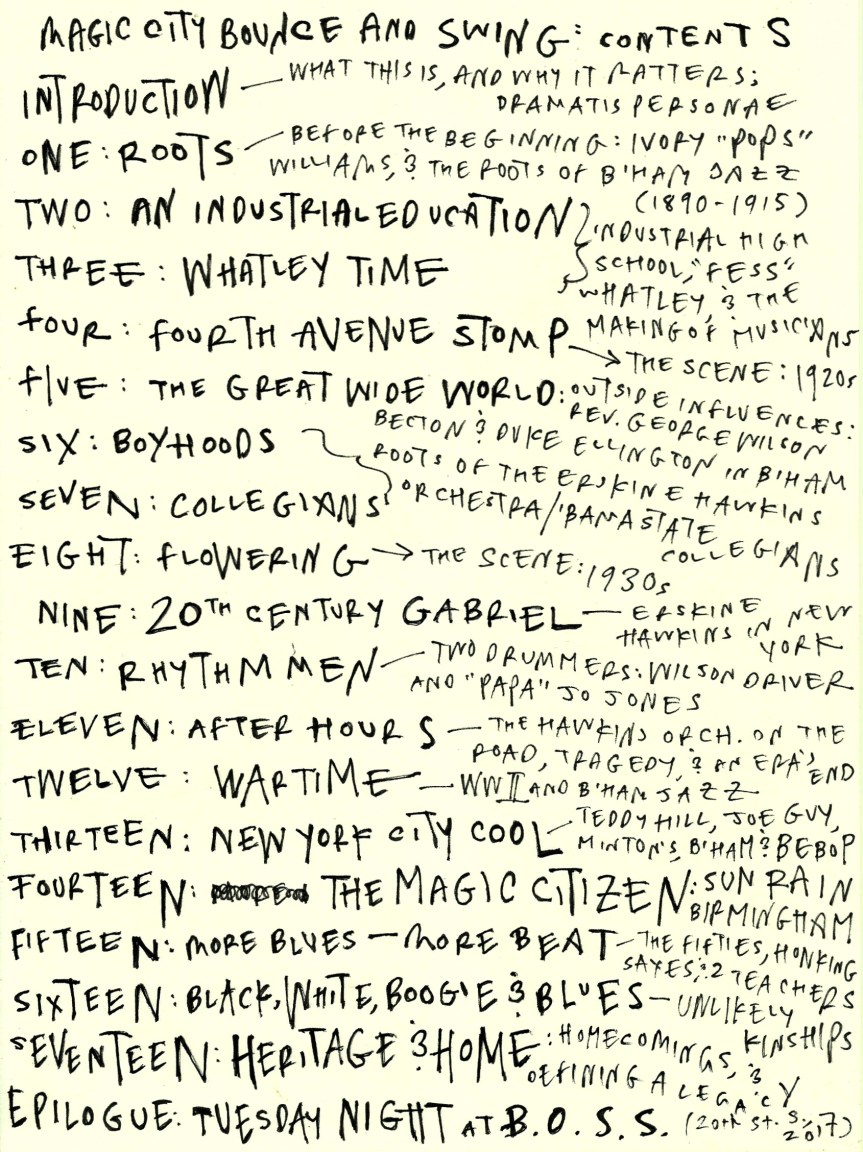

Magic City Bounce and Swing tells the story of one of American music’s most essential unsung communities.

In an era of pervasive segregation, African American educators in Birmingham, Alabama, created a pioneering high school music program that offered students a life outside the local mills and mines. After graduation, students trained under John T. “Fess” Whatley and other Birmingham bandmasters fanned out all over the country, joining the nation’s top jazz bands. They backed Bessie Smith on stage and on record and populated the bands of Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Louis Armstrong and others. The Erskine Hawkins Orchestra, an ensemble full of Birmingham players, became one of the swing era’s most popular and enduring dance bands, and their biggest hit—“Tuxedo Junction,” a tribute to their hometown scene—became an American anthem. When the country went to war, other Birmingham jazzmen filled the ranks of the Army, Navy, and Air Force bands that provided a soundtrack for the cause.

Often making their mark from the sidelines or behind the scenes—as composers and arrangers, sidemen, businessmen, mentors and teachers—Birmingham musicians exerted a broad influence on the popular culture of the nation. Drummer Jo Jones pioneered the shimmering, propulsive rhythm that came to define the sound of swing. Bandleader Teddy Hill helped launch the careers of some of the giants of modern jazz and, as manager of Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem, became a catalyst for the bebop revolution. Sun Ra—one of American music’s most inventive, iconoclastic originals—pushed the jazz tradition to its furthest-out, most exploratory fringes, communicating a new music for the cosmos. Other players remained in Birmingham, shaping the local scene and passing the tradition to new generations. The contributions of these musicians and others meant more than mere entertainment: long before Birmingham emerged as battleground in the struggle for civil rights, its homegrown jazz heroes helped set the stage, crafting a unique tradition of achievement, independence, innovation, and empowerment.

Drawing on troves of previously untapped sources—interviews, news reports, home recordings, and more—Magic City Bounce and Swing reveals, for the first time, the story of this remarkable community. Tracing the intersecting lives of its unforgettable cast of characters, the story crisscrosses an America that’s been largely forgotten: from segregated high school band rooms to the swanky gala dances of the South’s black elite, from jazz-fueled religious revivals to smoky urban night clubs, from touring vaudeville tent shows to the world’s most glittering ballrooms. What emerges is nothing less than a secret history of jazz—and a joyful exploration into the hidden roots of America’s popular culture.

*

That’s it. Thoughts?

P. S. Thanks for reading (and commenting)! If you’re curious about the book above, please in the meantime check out my previous book, Doc, which was just reissued in paperback. If you’d like to see more of this blog, look for the “Follow” option at the top of this page. If you want more music-related stuff, please check out my radio show. And if you just want to say hello, just say hello!

You must be logged in to post a comment.