Good news!

I’m thrilled to announce the publication of my book Magic City: How the Birmingham Jazz Tradition Shaped the Sound of America.

Officially the book is out on November 28, but pre-orders have already begun trickling out to mailboxes and stores. Please take a moment to order a copy, anywhere you get your books. (As always, I recommend your local independent bookstore, or else this good company: bookshop.org.)

If you happen to live in Birmingham, Alabama, please join us for the book release party at the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame on Saturday, Dec. 2. I’ll also be speaking at a public event hosted by the Birmingham Historical Society on Dec. 3. In the meantime, I’m lining up some book events for the new year, here in Alabama and beyond; if you’d like to host an event in your town, please just shoot me a message: burgin@southernmusicresearch.org.

Here’s a synopsis from the publisher:

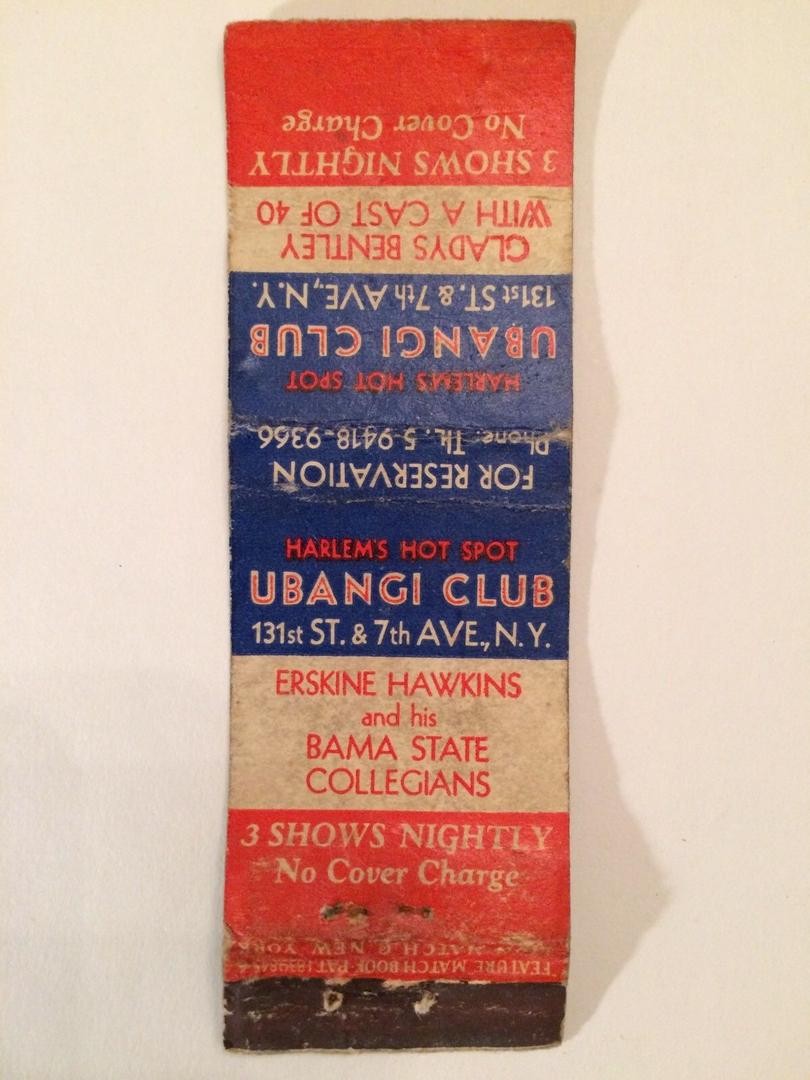

Magic City is the story of one of American music’s essential unsung places: Birmingham, Alabama, birthplace of a distinctive and influential jazz heritage. In a telling replete with colorful characters, iconic artists, and unheralded masters, Burgin Mathews reveals how Birmingham was the cradle and training ground for such luminaries as big band leader Erskine Hawkins, cosmic outsider Sun Ra, and a long list of sidemen, soloists, and arrangers. He also celebrates the contributions of local educators, club owners, and civic leaders who nurtured a vital culture of Black expression in one of the country’s most notoriously segregated cities. In Birmingham, jazz was more than entertainment: long before the city emerged as a focal point in the national civil rights movement, its homegrown jazz heroes helped set the stage, crafting a unique tradition of independence, innovation, achievement, and empowerment.

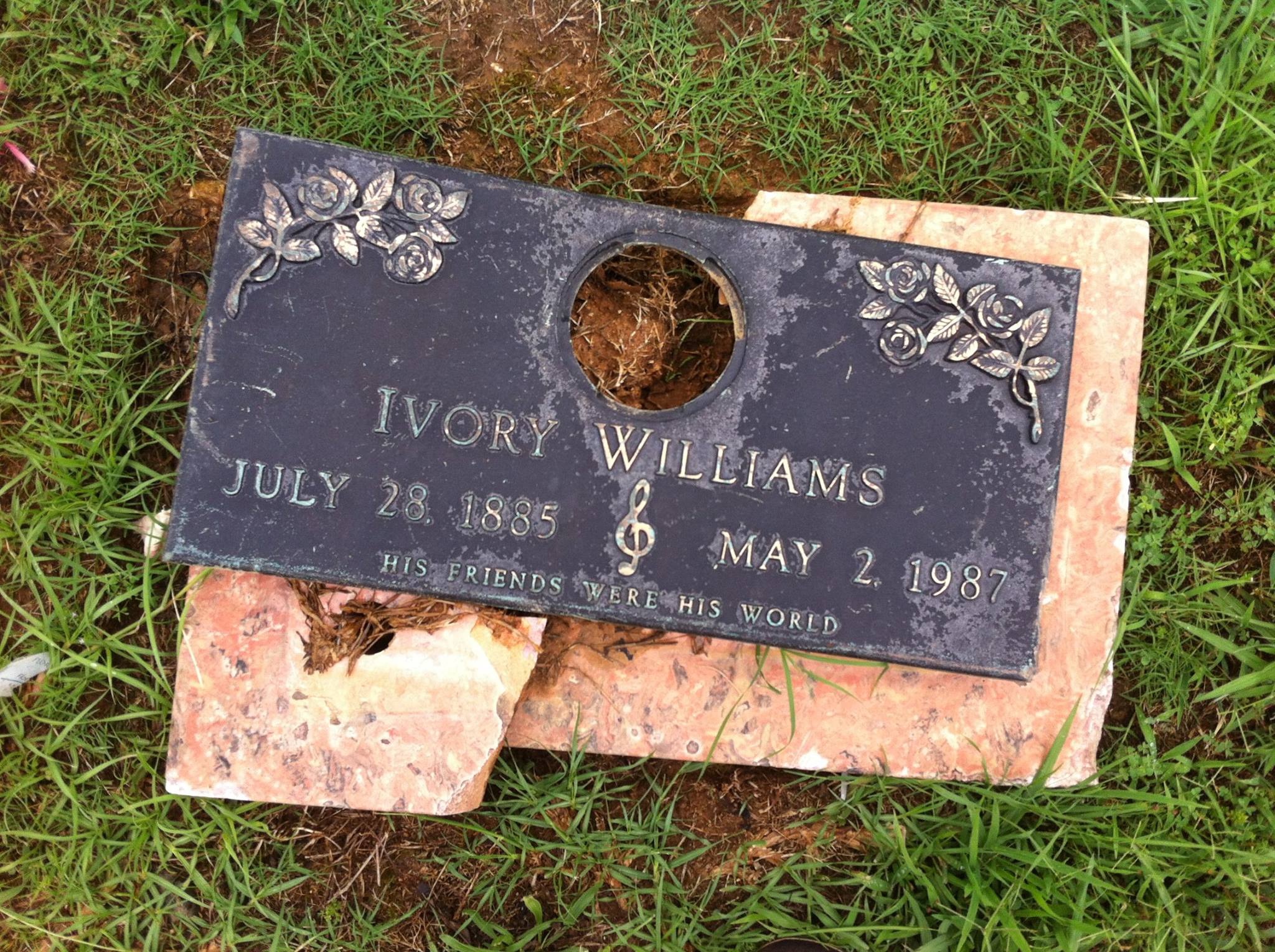

Blending deep archival research and original interviews with living elders of the Birmingham scene, Mathews elevates the stories of figures like John T. “Fess” Whatley, the pioneering teacher-bandleader who emphasized instrumental training as a means of upward mobility and community pride. Along the way, he takes readers into the high school band rooms, fraternal ballrooms, vaudeville houses, and circus tent shows that shaped a musical movement, revealing a community of players whose influence spread throughout the world.

While I’m here, I’ll acknowledge that this website and blog have been dormant for quite a long time now. I started the site in 2016, largely with the purpose of documenting the development of this book-in-progress. (In 2016, the book had already been five years in progress — so this thing has been quite a while in the making.) A lot has happened since I last posted anything here: for one thing, I started a nonprofit, the Southern Music Research Center, which officially launched this April with the debut of our website, a growing online archive full of rescued recordings, oral histories, rare photos, and other artifacts from a wide range of music communities and traditions. I hope you’ll take some time to explore our archival collections at southernmusicresearch.org. Among other things, you’ll find lots of material there related to my research on Birmingham jazz: photos, newspaper ads, recordings, interviews, funeral programs, magazines, ephemera, and more.

Basically, there’s a lot to celebrate and to explore. I hope you’ll check out the site, and the book. Let me know what you think, and thanks.

— Burgin

You must be logged in to post a comment.