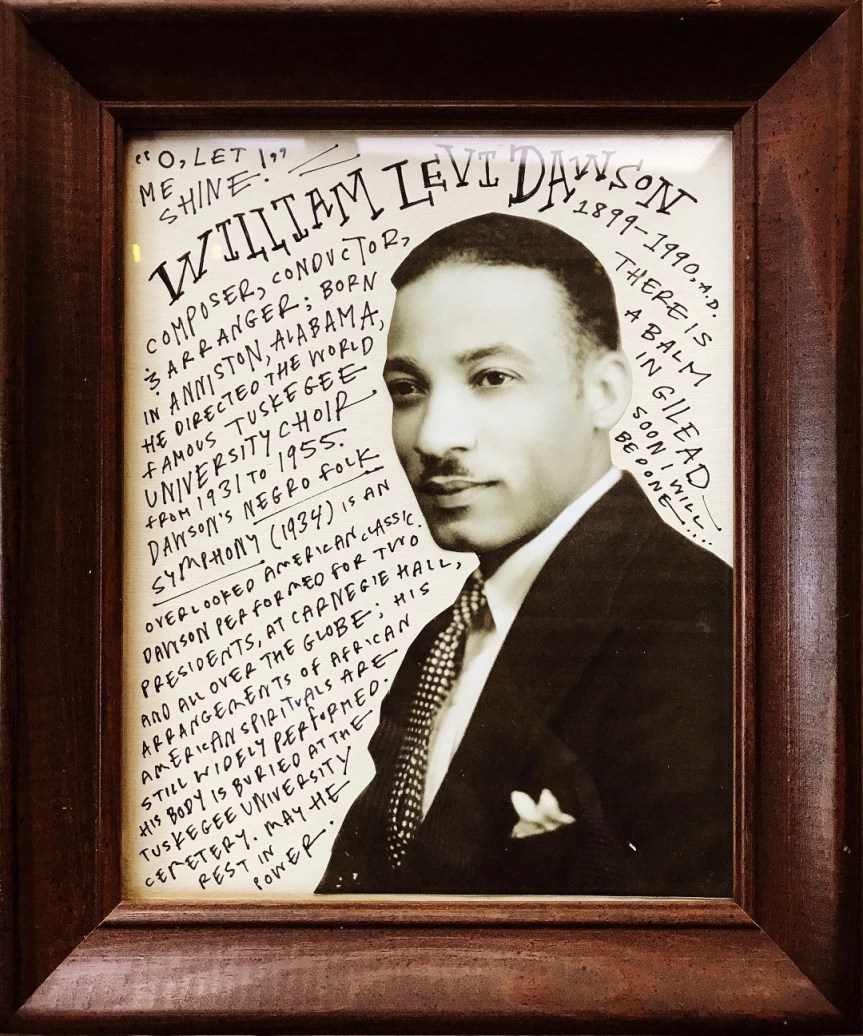

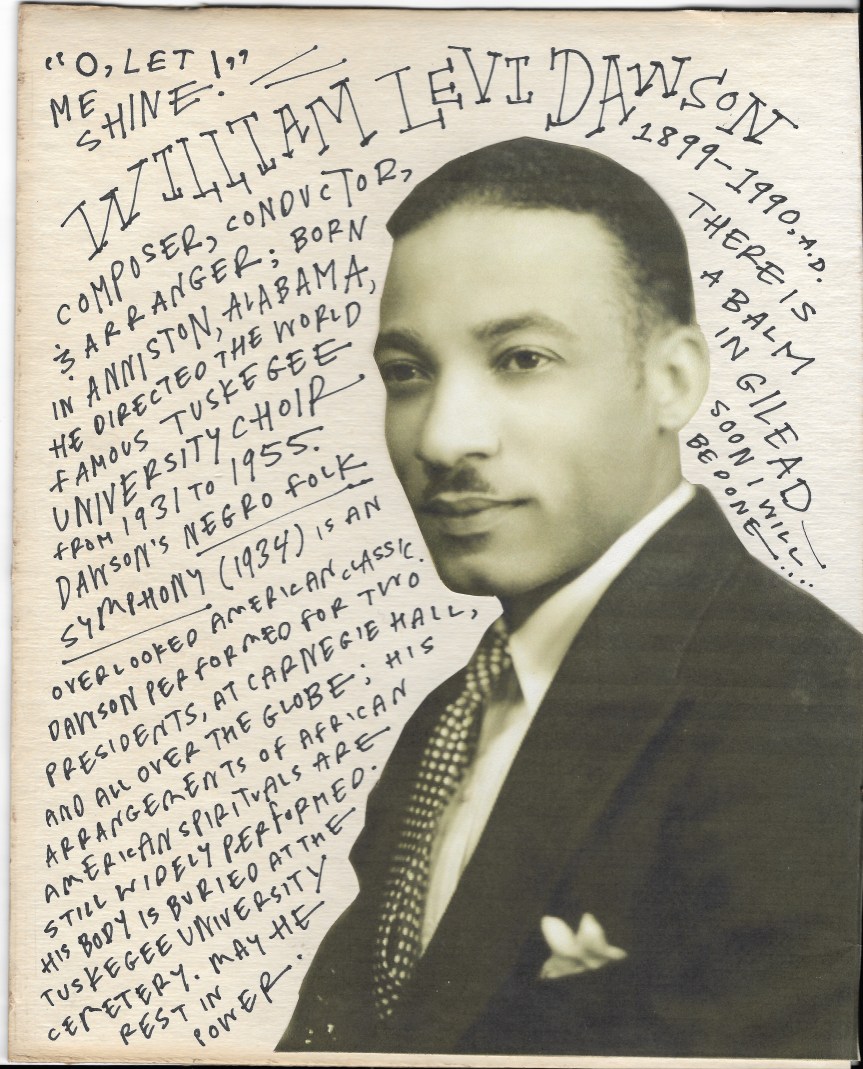

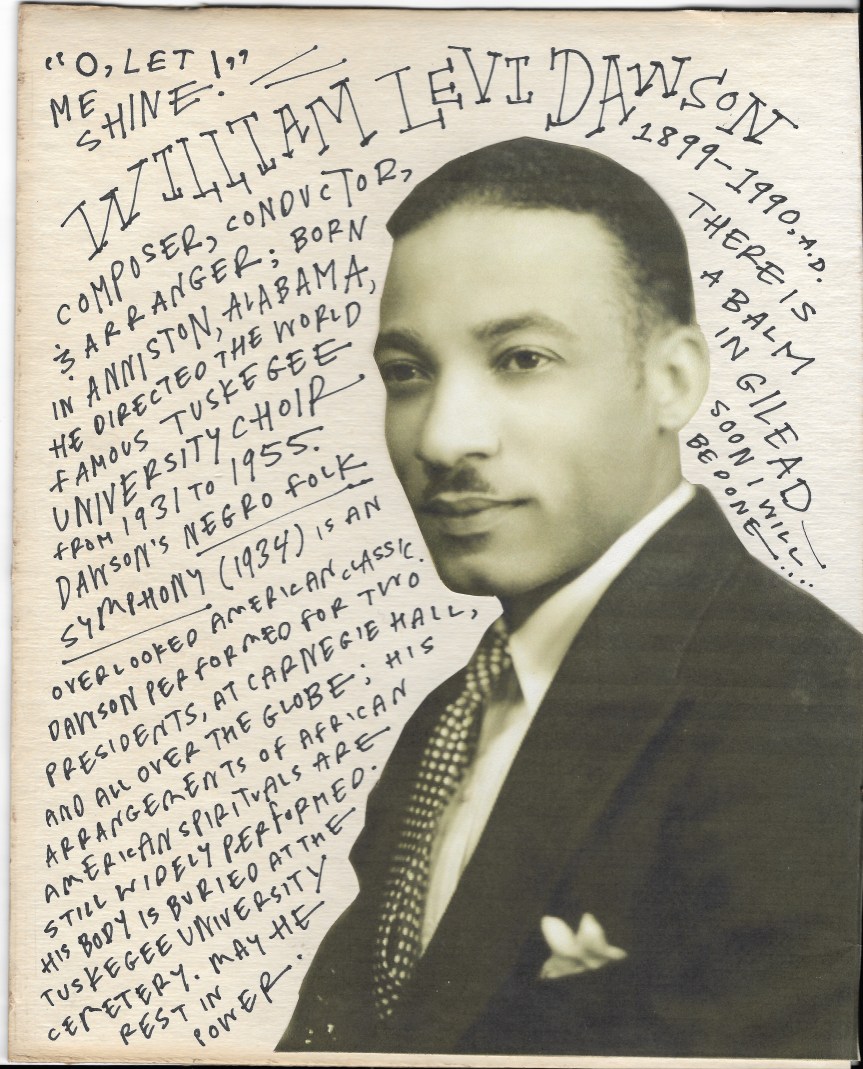

William Levi Dawson, the latest from my Book of Ancestors, a work in progress:

I started the Book of Ancestors a few months ago. It’s divided into three sections — “Family,” “Music,” and “Movement” — and will feature tributes to a range of “ancestors,” both literal and figurative, all from my home state of Alabama. (The “Movement” subtitle refers not only to figures from the Civil Rights Movement, but to a range of social movers whose lives represent numerous sorts of momentum, progress, and positive change.) I plan to be working at this off and on for a good little while, and thought I may as well post occasional developments here.

I made this tribute to Dawson last night while listening to his Negro Folk Symphony and to performances of the Tuskegee University Choir, recorded under his direction. I’d never heard of Dawson until very recently. A few weeks ago I came across this description in the WPA’s Alabama guidebook, first published in the 1930s:

“William Levi Dawson, director of the School of Music and the choir at Tuskegee Institute, is probably the State’s leading contemporary composer. Born in Anniston in 1899, Dawson has written in all forms and won the Rodman Wanamaker contest for composition in 1930 and 1931. Among his works are Negro Folk Symphony No. 1, first performed by the Philadelphia Symphony Orchestra in 1934, “Out in the Fields,” and “Ain’-a That Good News,” a cappella choruses, and “Break, Break, Break,” a choral with orchestra. Maude Cuney-Hare, in Negro Musicians and Their Music, estimates that Dawson is the first among “present cultivated Negro composers of whom much may be expected in the way of producing what will be the future American music.”

Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony was a huge deal when it was first performed. It was lauded by Alain Locke, one of the principal architects of the Harlem Renaissance, singled out as both a masterwork in itself and as a harbinger of great things to come. The original Philadelphia audience broke custom by erupting into applause more than once before the first performance was finished; when it was over the crowd called Dawson out for multiple bows. Performances followed at Carnegie Hall, whose crowds were similarly enthusiastic and unrestrained. Listeners across the country tuned in to hear the piece performed live over the radio waves. “One is eager to hear it again and yet again,” cheered a critic for the New York World-Tribune. A review in the New York American newspaper declared it “the most distinctive and promising American symphonic proclamation which has been so far achieved.” It was 1934, and Dawson was a black man from Alabama; his achievement was an historic one.

In the original program notes, Dawson wrote this:

“This Symphony is based entirely upon Negro folk-music. The themes are taken from what are popularly known as Negro spirituals, and the practiced ear will recognize the recurrence of characteristic themes throughout the composition… . In this composition the composer has employed three themes taken from typical melodies over which he has brooded since childhood, having learned them at his mother’s knee.”

Two years before the symphony’s debut, Dawson had explained his ambitions to a reporter for the Associated Press. “I’ve not tried,” he said, “to imitate Beethoven or Brahams, Franck or Ravel — but to be just myself, a Negro. To me, the finest compliment that could be paid my symphony when it has its premiere is that it unmistakably is not the work of a white man. I want the audience to say: ‘Only a Negro could have written that.”

Regrettably, in the years since its debut, Dawson’s landmark work has faded into obscurity. Dawson remained a respected public figure for years to come, but not for his orchestral compositions: under Dawson’s direction the Tuskegee University Choir gained international renown, touring and broadcasting widely and performing for the likes of Herbert Hoover and Franklin Roosevelt. Dawson emerged as an influential choral arranger and composer, and many of his spiritual arrangements have became American staples. He revisited and revised his original symphony several times in the years after its debut, but his attentions no longer centered on orchestral composition. In recent years, a few scholars have wondered over the gradual neglect of Dawson’s symphony and have advocated for its place in the American canon (see, for example, Gwynne Kuhner Brown’s “Whatever Happened to William Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony?” or John Andrew Johnson’s “William Dawson, ‘The New Negro,’ and His Folk Idiom”). While many of Dawson’s choral arrangements are still performed today — his most active lingering legacy — the name William Levi Dawson has been largely, and unjustly, forgotten.

So here he is, in my growing Book of Ancestors.

More to come.

Stay tuned.

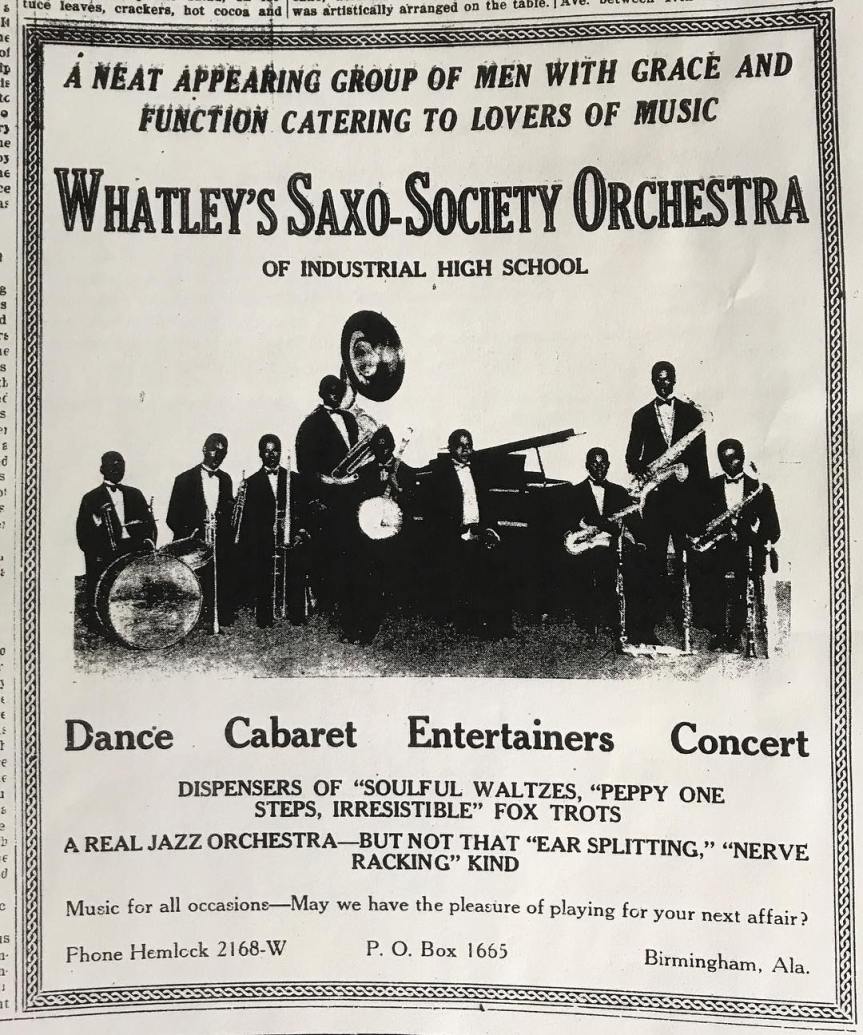

P. S. Want to see more things like this? Stay in the loop by following the blog: you can sign up on the top, righthand side of this page (or scroll to the bottom, if you’re viewing on a phone) to receive new posts in your email inbox. You can also follow @lostchildradio on Instagram and “like” my book and/or radio show on Facebook. You can also(!!) purchase my book with Alabama jazzman “Doc” Adams online or at your local bookstore. Heartfelt thanks, sincerely, for any / all of the above.

You must be logged in to post a comment.