Every day this month I’ve been posting to Instagram and Facebook a new, old photo from Birmingham, Alabama’s rich and significant, unsung jazz history. You can see the first five posts here. Here are ten more …

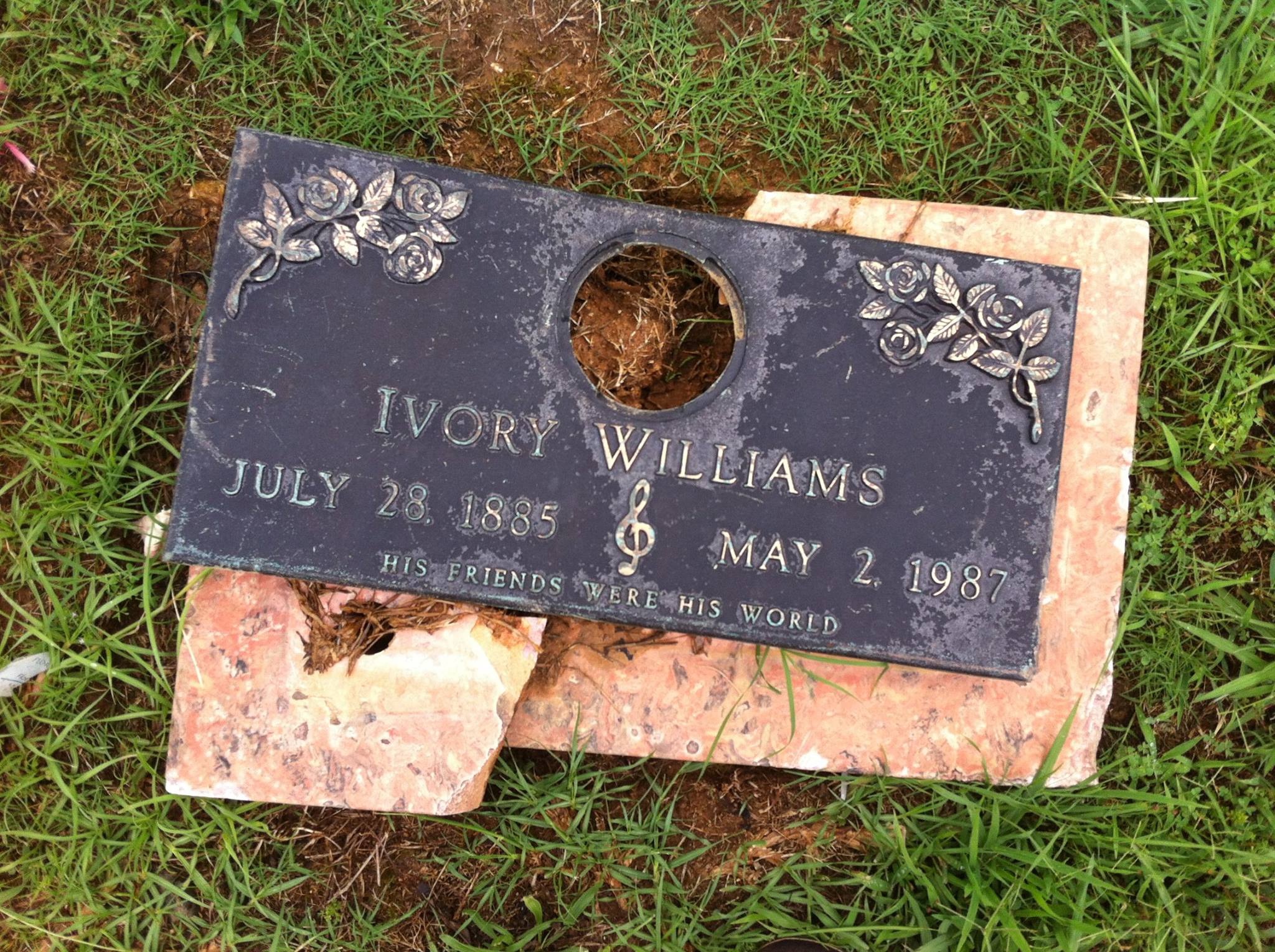

January 5. This is Frank Adams and his band, sometime in the 1950s. L to R: Ivory “Pops” Williams (on bass, face obscured by mic), Selena Mealing, Frank Adams, and Martin Barnett. Adams had come back to Birmingham after studying at Howard University and picking up short-term work with the Duke Ellington Orchestra, Louis Jordan’s Tympany Five, and other groups. Inspired by the high energy, humor, and movement of the Jordan group, he insisted his own band incorporate choreographed dance moves to liven up a local scene that had grown pretty stiff and staid. Fess Whatley–Birmingham’s “Maker of Musicians” and one of Adams’s mentors–called small combos like this one “bobtail bands” (because “they had their tails cut off”) and complained that they took work away from the larger dance orchestras. Frank Adams–in later years, he’d be affectionately nicknamed “Doc”–became a fixture of the Birmingham jazz scene and one of the city’s last links to its early jazz roots. Check out my book with Adams (Doc: The Story of a Birmingham Jazz Man), now available in paperback from the University of Alabama Press, and stay tuned all this month for more history and rare photos.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

January 6. Nat King Cole addresses the crowd at Birmingham’s Municipal Auditorium, just after being attacked onstage. Every day this month I’m posting a photo from Birmingham’s jazz history. Singer and pianist Nat King Cole (a native of Montgomery, AL, and a national star) was only three songs into his April, 1956 performance, when three assailants rushed the stage and knocked the singer to the ground. Cole was rushed backstage and, after a flurry of confusion, the attackers were arrested. The men belonged to the virulently segregationist North Alabama Citizen’s Council, founded by Klansman Asa Carter. In a few years, Carter would work as speechwriter for George Wallace and pen the governor’s famous pledge: “Segregation today, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” But first, in the 1950s, Carter was railing publicly against jazz, rock-and-roll, and any other form of “Negro music,” which he warned was “Communistic,” “animalistic,” and would “mongrelize America.” In Nat Cole, he found a symbolic target for his fury. After the night’s initial chaos subsided, King stepped briefly back onstage: “I just came here to entertain,” he told the crowd. “I thought that was what you wanted.” He quickly left the stage, and the state. Swipe left to see Cole backstage after the incident, and an editorial in Billboard. (First photo: Detroit Public Library. Second photo: Bettmann/Bettmann Archive.)

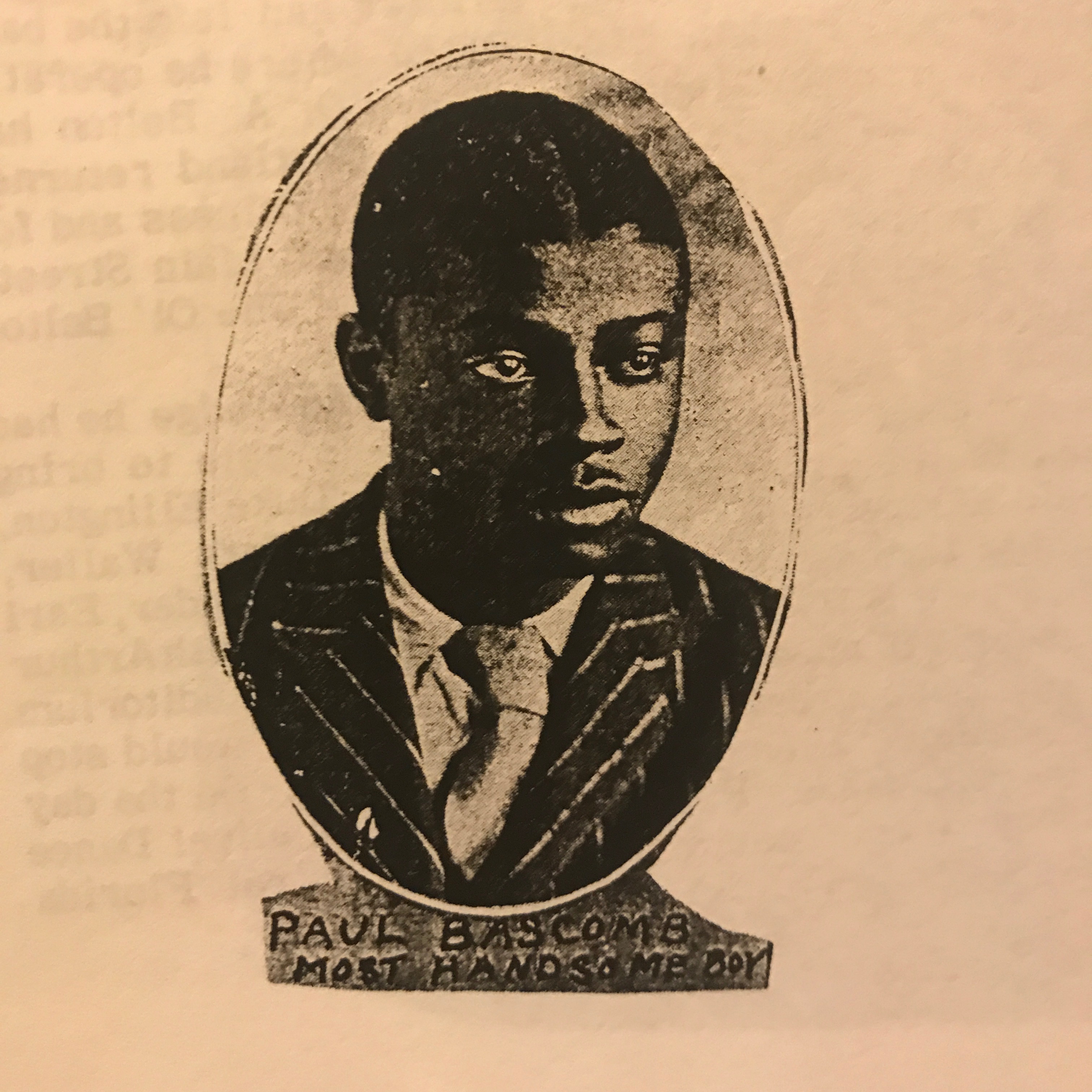

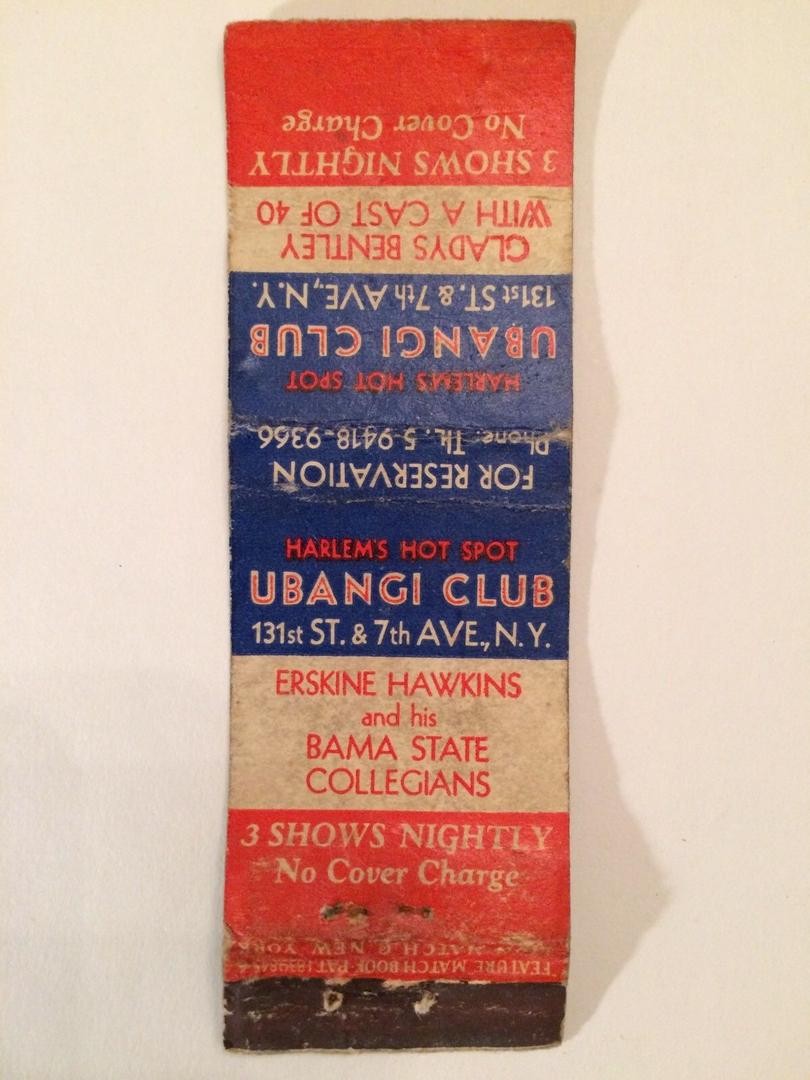

January 7. Every day this month I’m posting a photo from Birmingham, Alabama’s jazz history. Here’s tenor sax player Paul Bascomb (voted Most Handsome Boy in his first year at Alabama State Teachers College in Montgomery—now Alabama State University.) Bascomb arrived at the school in 1928 and started the first jazz band on campus. Recognizing the group’s immediate popularity and potential—and facing the deep financial woes of the Great Depression—the school’s president, H. Councill Trenholm, recruited Bascomb’s band into the service of the college. As the ‘Bama State Collegians, the group traveled the South, raising money for the college; their earnings helped Alabama State stay afloat through the depression, helping pay basic utilities and salaries. Meanwhile, the ‘Bama State Collegians grew into the southeast’s most popular African American dance band. Almost the entire group came from Birmingham, having learned music at Industrial High School or the Tuggle Institute. Soon trumpeter Erskine Hawkins would emerge as leader, and the group would go professional as the Erskine Hawkins Orchestra. This photo is included in Gadsden, Alabama, trumpeter Tommy Stewart’s unpublished history of the ‘Bama State Collegians; a later alum of that band, Stewart has amassed a rich trove of materials related to the group’s history.

January 8. Every day this month I’m posting a photo from the history of Birmingham jazz. Here’s trumpeter Wilbur “Dud” Bascomb, a player who helped bridge the big band era with the advent of modern jazz. Miles Davis got his start memorizing Dud Bascomb’s solos note for note; so did Fats Navarro, Idrees Sulieman, and other bebop pioneers. Dizzy Gillespie called him “the most underrated trumpeter” and added: “He was playing stuff in Erskine Hawkins’ band back in 1939 that was way ahead of its time.” Bascomb played the definitive, much-copied trumpet solos on such Hawkins hits as “Tuxedo Junction”; since Hawkins was a trumpeter, too, many record buyers never knew it was Bascomb, not the bandleader, behind those classic solos. Soft-spoken and unassuming, Bascomb was content staying out of the spotlight. For a while he played with Duke Ellington (seen here) but he preferred the easy-going camaraderie of the Hawkins group — most of whose members had been friends since their childhoods in Birmingham. See yesterday’s post about Dud’s tenor-playing brother, Paul — and stay tuned for much more Birmingham jazz history all this month.

January 9. Souvenir photograph of guests at the Grand Terrace, just outside Birmingham on Highway 78. Every day this month I’m posting a photo from the history of Birmingham jazz. The Grand Terrace, named for the celebrated Chicago ballroom, was one of the premier entertainment and dance spots for African Americans in Birmingham in the 1940s and ‘50s. Owned by “Foots” Shelton, the venue hosted local bands like that of pianist John L. Bell and was a frequent stopping point for a young Ray Charles, B.B. King, Louis Jordan, and others. Many social savings clubs and other local black organizations held their regular gatherings in the Grand Terrace’s Rainbow Room, and radio station WJLD hosted occasional remote broadcasts from the venue. Wooden cabins behind the club put up traveling musicians for the night, and vacant cabins could be rented by patrons for quick sexual liaisons. Because of a discrete deal with the notorious Bull Connor, Birmingham’s Commissioner of Public Safety, the Grand Terrace was one of the few places in town that sold liquor on Sunday nights. Thanks to Patrick Cather for this great photo.

January 10. This one’s a little battered, but it’s a gem: here’s Frank Adams again, along with other local musicians at Birmingham’s Club 2728, backing a female impersonator, sometime in the 1950s. This photo’s included in my book “Doc,” which tells the life story of Frank Adams and celebrates its paperback release today. If you’re in Birmingham, join me at Little Professor tonight at 6 for the release celebration and a book talk; if you’re somewhere else, ask for it from your own book dealer, or else find it online. Every day this month I’m posting a photo from Birmingham’s jazz history. There’s a lot going on in this one.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

January 11. Sun Ra would never say he was born in Birmingham; he “arrived” there in 1914, but he’d really come from outer space. Birmingham had been created as an industrial hub for the South, and its founders and early boosters had declared it “The Magic City,” thanks to its sudden, near-overnight growth. A huge sign at the Terminal Station welcomed visitors to The MAGIC CITY, and Sun Ra—or Herman “Sonny” Blount, in those days—grew up right across the street from the sign. The phrase lodged in his imagination. His 1965 album, The Magic City, nodded to his roots while conjuring up an another world entirely. A landmark moment in Sun Ra’s career–with its title track stretching more than twenty-seven minutes—the album was the bandleader’s most ambitious, experimental release to date, a work that pushed his music and musicians into new territory and cemented his place as a cosmic visionary. Every day this month I’m posting a photo from the history of Birmingham jazz. Stay tuned for more—including some rarities from Sonny Blount’s early Birmingham days.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

January 12. Here are the first 5 inductees to the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame, founded in 1978 to honor Birmingham’s rich jazz legacy. From L to R: Sammy Lowe, composer & arranger; Erskine Hawkins, trumpeter & bandleader; Frank Adams, alto sax player & clarinetist; Amos Gordon, alto sax player & clarinetist; Haywood Henry, baritone sax player & clarinetist. John T. “Fess” Whatley, the father of the local jazz community, was also inducted posthumously that year. Lowe, Hawkins, and Henry were all key members of the Erskine Hawkins Orchestra, and Lowe was a prolific arranger in the pop field of the 1950s and ‘60s. Adams, Gordon, and Whatley were influential music teachers as well as accomplished musicians. Later inductees to the hall of fame include Sun Ra, Jo Jones, Teddy Hill, “Pops” Williams, Paul & Dud Bascomb, and many others–stay tuned all this month, as I post more daily photos from the history of this remarkable, influential, and unsung jazz community.

January 13. If you’ve ever seen the B.B. King concert film “Live in Africa ’74,” you couldn’t have missed the stylish dude in the plaid jacket directing the band. That’s Hampton “Hamp” St. Paul Reese III, a product of Birmingham’s jazz scene — and a musician who became B.B. King’s right-hand-man. Reese was one of the many skilled arrangers and composers who came out of Fess Whatley’s Industrial/Parker High School classroom. Hamp was intellectual, hip, and one of a kind; he brought a new range to King and his music and became a favorite among King’s fans. In his autobiography, King called Reese “my overall tutor and teacher,” “my confidant and role model,” and “a brilliant arranger,” and he explained Hamp’s influence like this: “His thing was books, books, books. If you don’t know something, go to a book. Don’t sit around feeling sorry for yourself; don’t feel inferior; pick yourself up, get to a library, find the book, and learn what you need to learn. Until Hamp, I really didn’t understand what research was all about. Didn’t know that there’s a world of information just waiting for you.” Under Reese’s influence, King learned to play some clarinet and violin and even how to fly a plane. Reese’s instructions, King explained, were as transformative as they were simple: “‘Study,’ said Hamp. And study I did.”

January 14. Every day this month, I’m posting a photo from Birmingham, Alabama’s rich and unsung jazz history. In the summer of 1927, the Gennett record label set up a makeshift recording studio on the third floor of the Starr Piano store in downtown Birmingham, inviting musicians from all over the state to record. For two months Gennett set to wax a wide range of blues, gospel, Sacred Harp singing, old-time fiddling, preaching, popular dance tunes, ragtime piano—and the first recordings of Alabama’s jazz bands. Frank Bunch and his Fuzzy Wuzzies put down “Fourth Avenue Stomp,” a tribute to Birmingham’s thriving black entertainment and business district, and the Black Birds of Paradise cut the tunes listed in this advertisement. The Black Birds were based in Montgomery and were, for the most part, recent grads of Tuskegee University. The group was known to put on a show—trombonist and bandleader William “Buddy” Howard could play trombone with his feet—and they engaged in friendly if fierce “cutting contests” with the state’s top jazz bands, including Fess Whatley’s Jazz Demons. During the Depression the band fell apart, a few of its members refiguring for a while as the Black Diamonds. In the 1960s, blues researcher Gayle Dean Wardlow tracked down the last surviving members in Montgomery: “We were a pretty good little juke band,” banjo player Tom Ivery told him, “even if I have to say so myself.”

*

That’s it for now. I’ve got some more great photos coming up all this month, so please stay tuned. Follow my radio show, The Lost Child, on Instagram and Facebook for more. Thanks.

You must be logged in to post a comment.