I said when I started this blog that one big purpose of the site was to complement my book in progress, my history of Birmingham jazz. I promised to share updates and outtakes, excerpts and footnotes, and to shed some light on the daily(ish) struggle of getting this thing onto paper, and (eventually) out to the world.

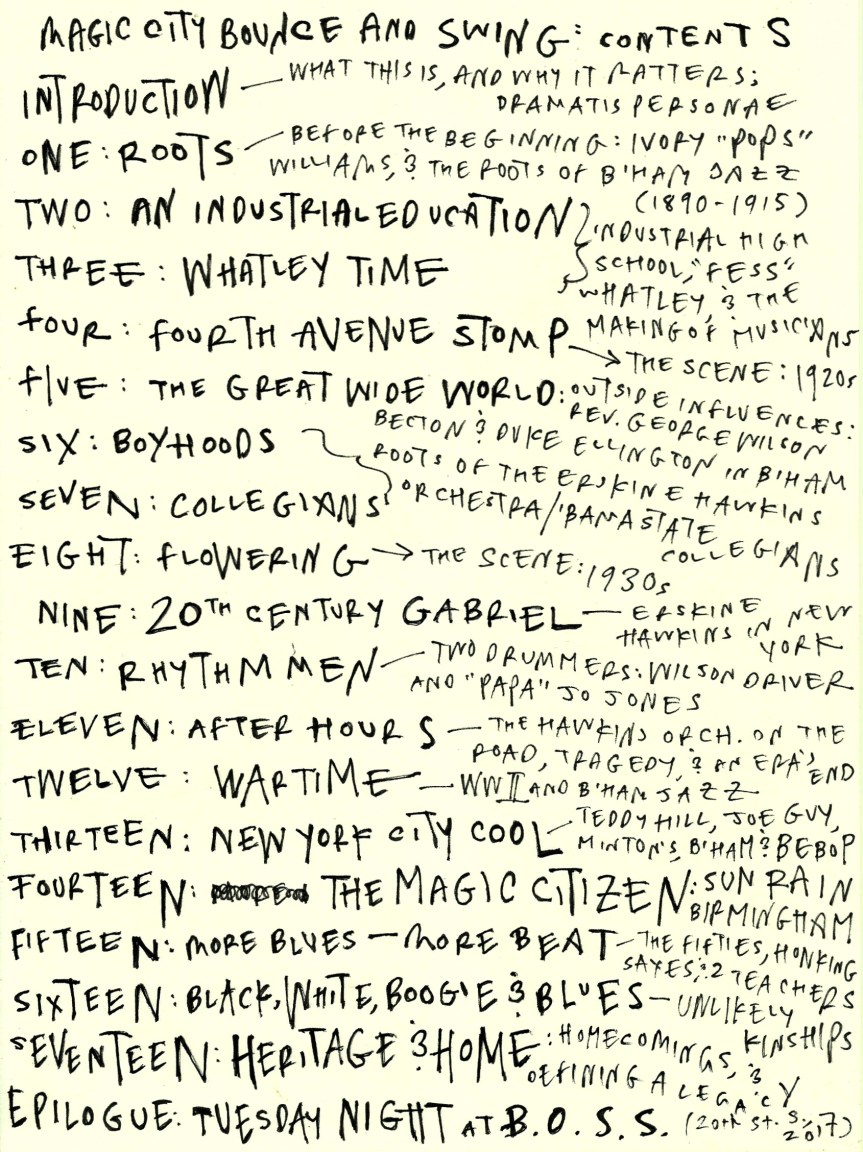

I haven’t posted a word about the book since then, so I thought I’d finally get to it today—and a table of contents seemed like a good, simple place to start. Sooner or later I’ll tell you more about why I’m writing this book, why I think the story’s so important, and what the overall gist of it is. In short, for now, it’s the story of how the unlikely city of Birmingham, Alabama helped shape the world of jazz—and of how jazz helped shape the city of Birmingham.

It’s a story that, for the most part, just hasn’t been told—at least not widely. People here in Birmingham don’t know it; neither do jazz lovers elsewhere. The book covers more or less a full century, revealing how the music programs of the city’s segregated black schools became a training ground for legions of jazz sidemen, arrangers, and a few notable bandleaders. I explore how a unique tradition of jazz musicianship helped generations of local players craft identities and experiences that transcended the limitations of the Jim Crow South—and examine how Birmingham players contributed actively, if largely from the sidelines, to the national culture of jazz. At the heart of the book is the swing era of the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s, but we see also how Birmingham helped beget bebop—and how one Magic Citizen, the iconoclastic, otherworldly Sun Ra, pushed jazz to its furthest limits, even as he drew from his own Birmingham roots.

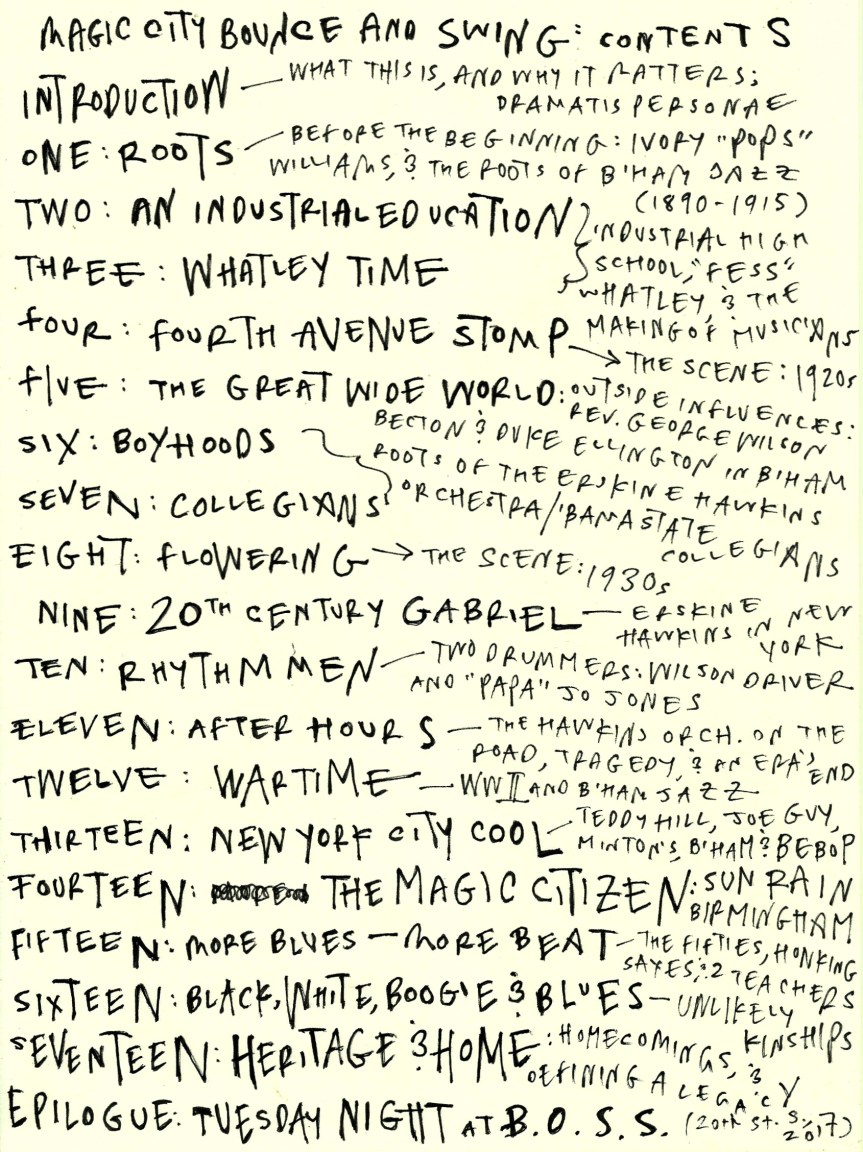

My working table of contents follows. The chapter titles may be a little cryptic on their own; my notes in the margins add a little bit of detail, but a table of contents is inherently a sort of tease. All but two of these chapters exist in some form now, though some are further along than others. The book title you see here—Magic City Bounce and Swing—is one I intend to discard once I finally find something better. I’ve been brainstorming for a few years now and for the life of me can’t come up with a title I like. I’ve searched song lyrics and quotes for the right phrase, and I keep coming up with nothing. I invite your title suggestions in the comments.

*

While we’re on the subject, an aside:

I spend a lot of time making lists of things, and the lists I’ve always enjoyed making most seem to be tables of contents. When I was a kid I was always making little books and filling them with stories, and always kicking them off on page one with a handy table of contents. I recently came across a little blank book my mom brought me home from the drugstore once, which I filled with two tiny novels: “Who’s Who?” and “The Christmas Mess.” It’s signed and dated 1988, so I guess I was eleven. It’s a pretty ambitious work, and it starts, of course, with a table of contents. For “Who’s Who” the TOC reads:

- Wadsworth – 1

- Spies – 9

- The Switch – 17

- Problems – 23

- Vampire Bob – 41

- Trouble – 47

- The Plan – 53

- Goodbye, Spies – 59

- Pop’s Diary – 63

Who wouldn’t want to read on, after that promise of things to come?

By seventh grade I was filling up notebooks and floppy discs with more tables of contents for more books I wanted to write or was secretly writing. In seventh and eighth grade I discovered real, written comedy: somehow before the internet ever happened, I’d managed to get my hands on copies of Monty Python’s two original Flying Circus books, published in the ‘70s, and Steve Martin’s absurdist collection Cruel Shoes, as well as The Complete Prose of Woody Allen, a compendium of Without Feathers and Getting Even and Side Effects. (I remember the Woody Allen book was on the sale table at Walden Books at the Montgomery Mall for $7.99 in a massive hardback, and I got a beat-up little blue and tan copy of Cruel Shoes at Montgomery’s one used-book store (that’s where I got Woody Guthrie’s Bound for Glory, too—see a previous post about that). I don’t know where I got the Monty Python books, maybe from a Signals catalogue or something similarly nerdy.)

Needless to say, my tables of contents reflected what I was writing, which reflected what I was reading: so in those days it was short, absurdist sketches and and silly comic essays. Every time I produced a few new pieces, I’d rearrange it all with a new table of contents.

In high school I discovered seriousness and poetry and I wrote many more tables of contents, outlining both my current writings and my future, unwritten—but carefully outlined—ambitions.

There were other tables, to be sure, in the years that followed. But jumping ahead to the table at hand:

Frank “Doc” Adams and I published our book Doc in 2012, and some months before it was done I wrote out my first table of contents for the book I’m writing now, the book outlined above. I’ve tweaked and rewritten this table of contents a million times. The contents and sequence have changed very little since I first charted it out: as the project has grown some chapters have split into half, or into three, but the overall flow sticks close to my initial conception. Sometimes I have to remind myself that rewriting the table of contents in my notebook, with minor adjustments, does not constitute writing, does not make a day’s work. Sadly, frankly, it’s on some days all I can do. Its’ tempting to let list-making stand in for true creative productivity; I remind myself often to resist the urge.

I might add this uncomfortable confession: that writing this book for so long I finally appreciate—I mean really appreciate—The Shining, a movie I’ve always loved but never before thought relatable. It’s not a happy revelation. I image Glory, horror-stricken, flipping through pages and pages of what I’ve written so far and discovering it’s all the same thing, over and over again. The same table of contents, the same chapters, the same sentences, revealing in their endless repetition my descent into madness. All work and no play… My own stomach sinks when I pick up my latest print-out: haven’t I typed out and held these words in my hands a thousand times already? I flip through my notebooks and find uncountable iterations of the same basic sequence and titles: Introduction; Roots; An Industrial Education …

I do make progress, though, little by little. And I stand proudly by my table—as the contents themselves slowly catch up to its promise.

(In the meantime, please: somebody send me a title.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.