One hundred and six years ago today, in the Magic City of Birmingham, a spaceways composer and bandleader arrived for the first time on Earth.

All his life, Sun Ra claimed to have come from outer space. He spoke of abstract other-worlds and alternate planes of existence, offering through his music a portal to other realities. For decades, he built around himself a personal mythology that rejected any earthly attachments. He may have grown up in that Alabama city of Birmingham, but he hadn’t been born there, he’d insist: he’d “arrived,” “combusted,” or “appeared,” sent from the cosmos to teach new truths to humankind. He left the city in 1946 and, as far as we know, didn’t return for decades. The place, it seemed, was irrelevant to his music and his mission.

His sister, Mary Blount Jenkins, balked at her brother’s refusal to acknowledge any earthly family or home. “He was born at my mother’s aunt’s house,” she told The Birmingham News in 1992, “over there by the train station. I know, ‘cause I got on my knees and peeped through the keyhole.

“He’s not,” she said, “from no Mars.”

For all his otherworldliness, Sun Ra was steeped in and shaped by the culture of his hometown. Herman “Sonny” Blount grew up in a fertile local jazz scene, a protégé of bandmaster John T. “Fess” Whatley, Industrial High School’s celebrated “Maker of Musicians.” By the time he graduated high school, in the spring of 1934, he was already leading his own band. Soon the Sonny Blount Orchestra was drawing acclaim across the Southeast.

Birmingham was full of musicians, many of whom would make significant marks on the sound and culture of jazz. Sun Ra’s generation of Birmingham players included the trumpeter-bandleader Erskine Hawkins and most members of his popular dance band; drummer Jo Jones, whose work with Count Basie remade the very rhythm and shimmer of swing; bandleader and businessman Teddy Hill, who turned Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem into the epicenter of the developing bebop sound. Other Birmingham instrumentalists worked in the bands of Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Earl Hines, Cab Calloway, Benny Carter, Billie Holiday. To make their careers in music, they left the South to find work in the jazz capitals of the nation—Chicago, New York, Kansas City—but all of them, even Sun Ra, were shaped first in the same thriving music scene back home.

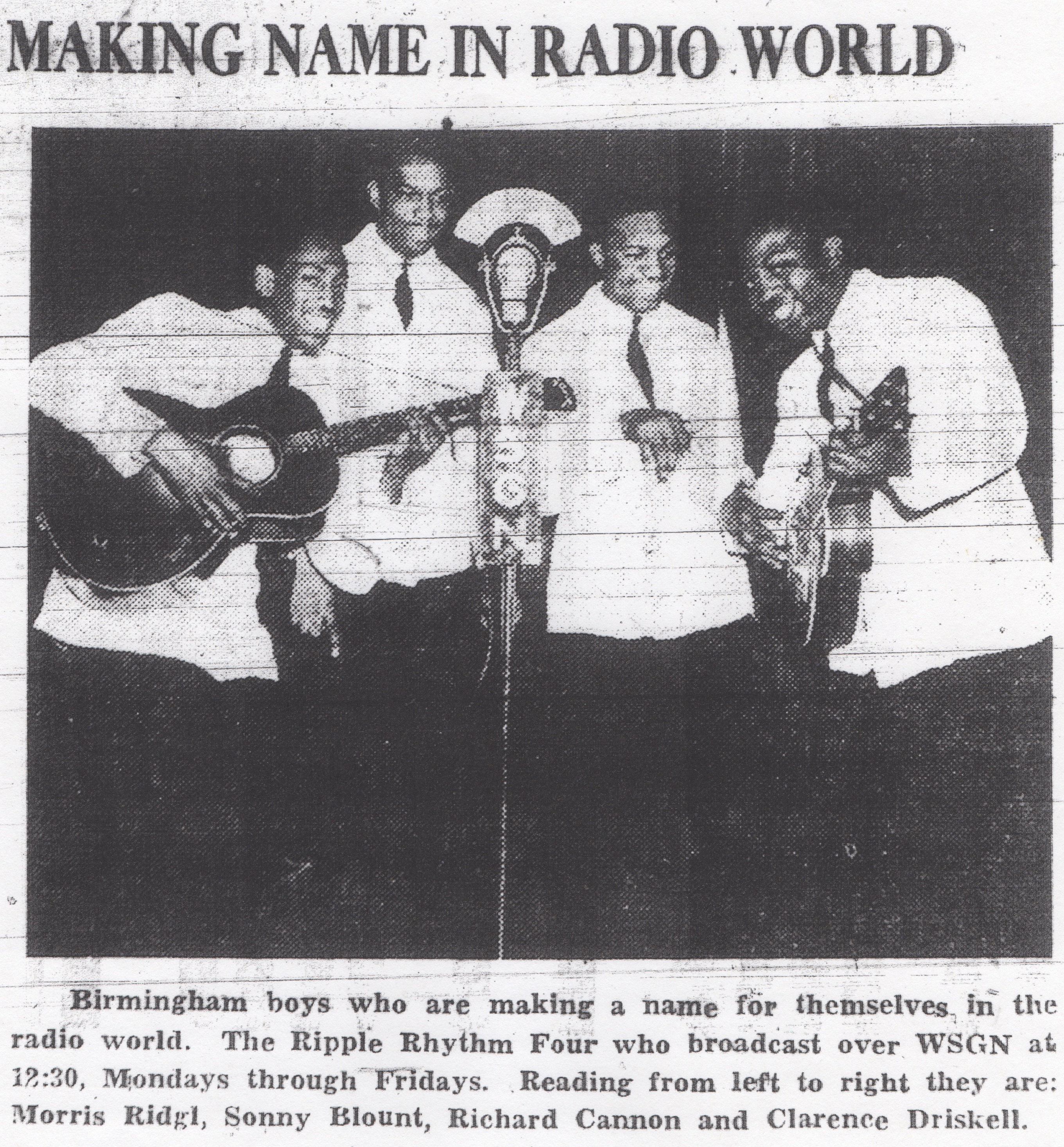

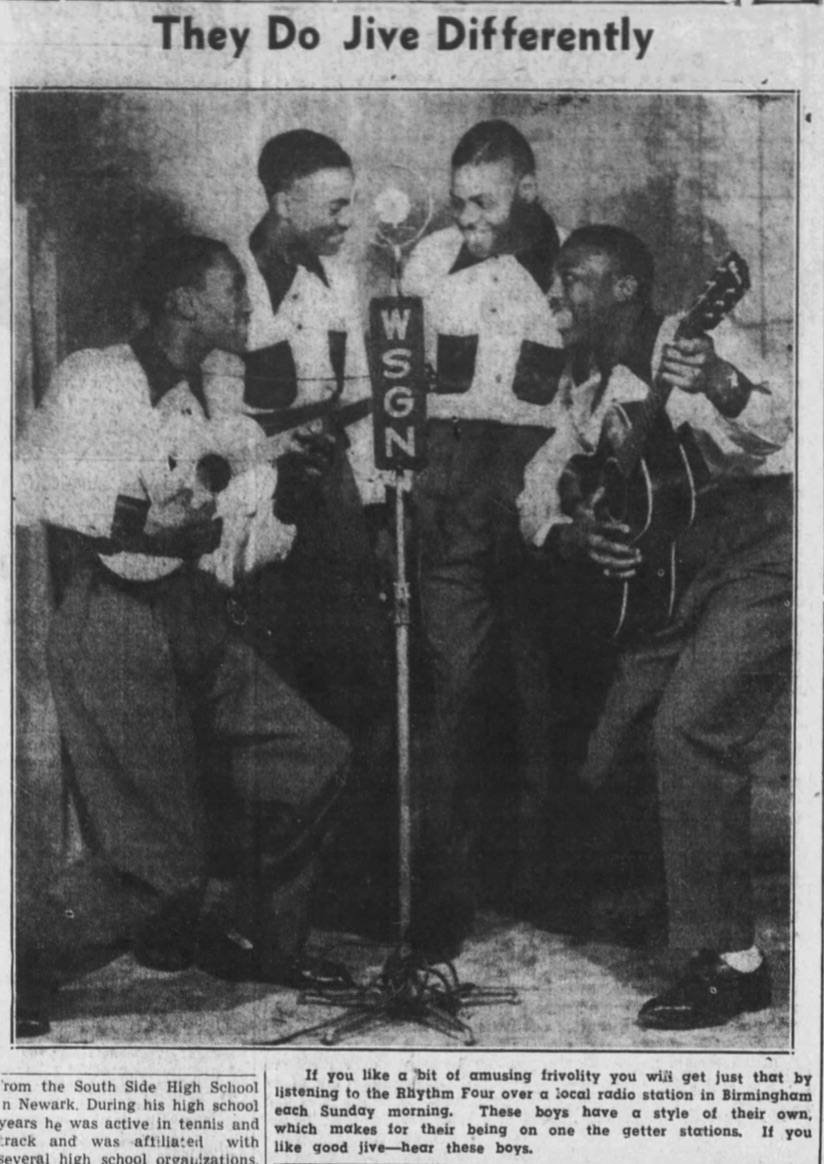

Local newspaper clippings from Sonny Blount’s years in Birmingham offer fascinating glimpses into the ear(th)ly roots of an enduring jazz icon. Below are several discoveries from my ongoing research into this history, presented in celebration of Sonny’s “arrival day” today. I’ve divided the post into two sections: first, a couple of rare early photos, and a look at Sonny’s vocal quartet, the Rhythm Four; then, a very brief survey of some of the venues and events where Sonny honed his role as bandleader in the early 1940s.

Together, these snatches of information help flesh out a portrait of the man who would become Sun Ra.

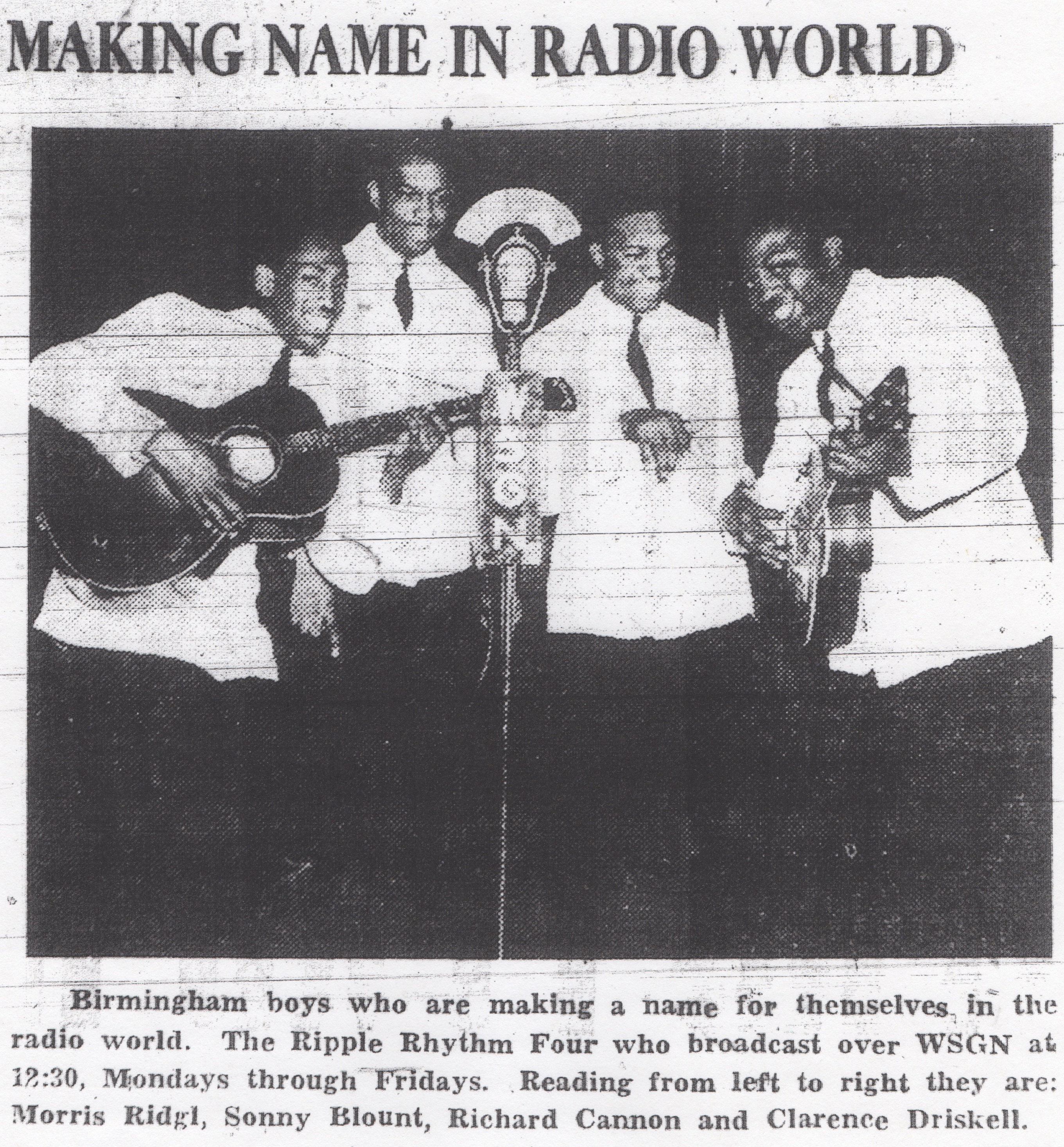

Part One: The Rhythm Four — Making a Name in Radio World

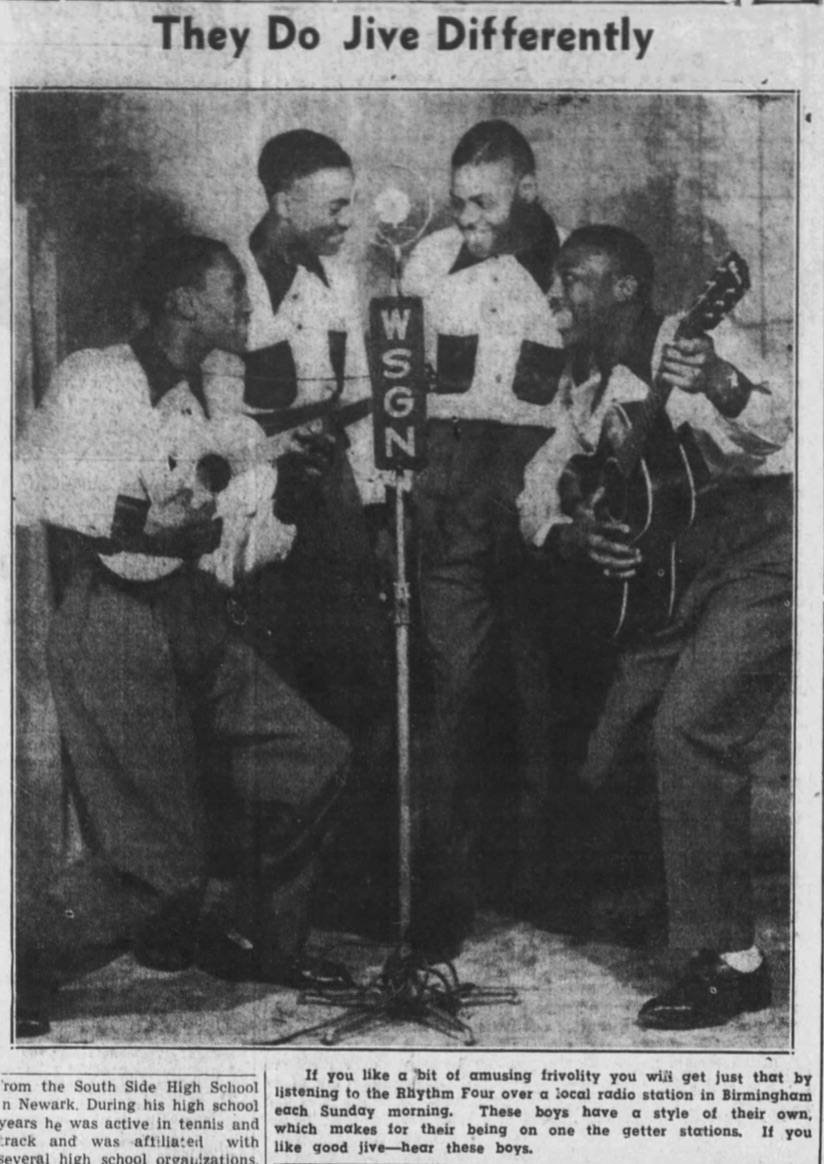

This photo from October, 1940—and a similar photo from the same session, below—are among the earliest known images of Sun Ra. That’s him, second from left, in a quartet called the Rhythm (or Ripple Rhythm) Four. Between 1939 and 1943, the group broadcast five days a week over radio station WSGN, their fifteen-minute midday segments squeezed into a crowded, diverse line-up of news programs, “hillbilly” bands, society dance orchestras, and more. They were sponsored first by R. C. Cola, then by the Ripple tobacco company—hence the “Ripple” that was sometimes added to their name. I first discovered this image above while scrolling through old microfilmed issues of the Birmingham World, a local African American newspaper, archived on the third floor of Birmingham’s central library. The same photo appears, around the same time, in the Weekly Review, an entertainment weekly that served the city’s black community for a few years in the ‘40s. The photo below presents the band in another pose; again Sonny is second from left.

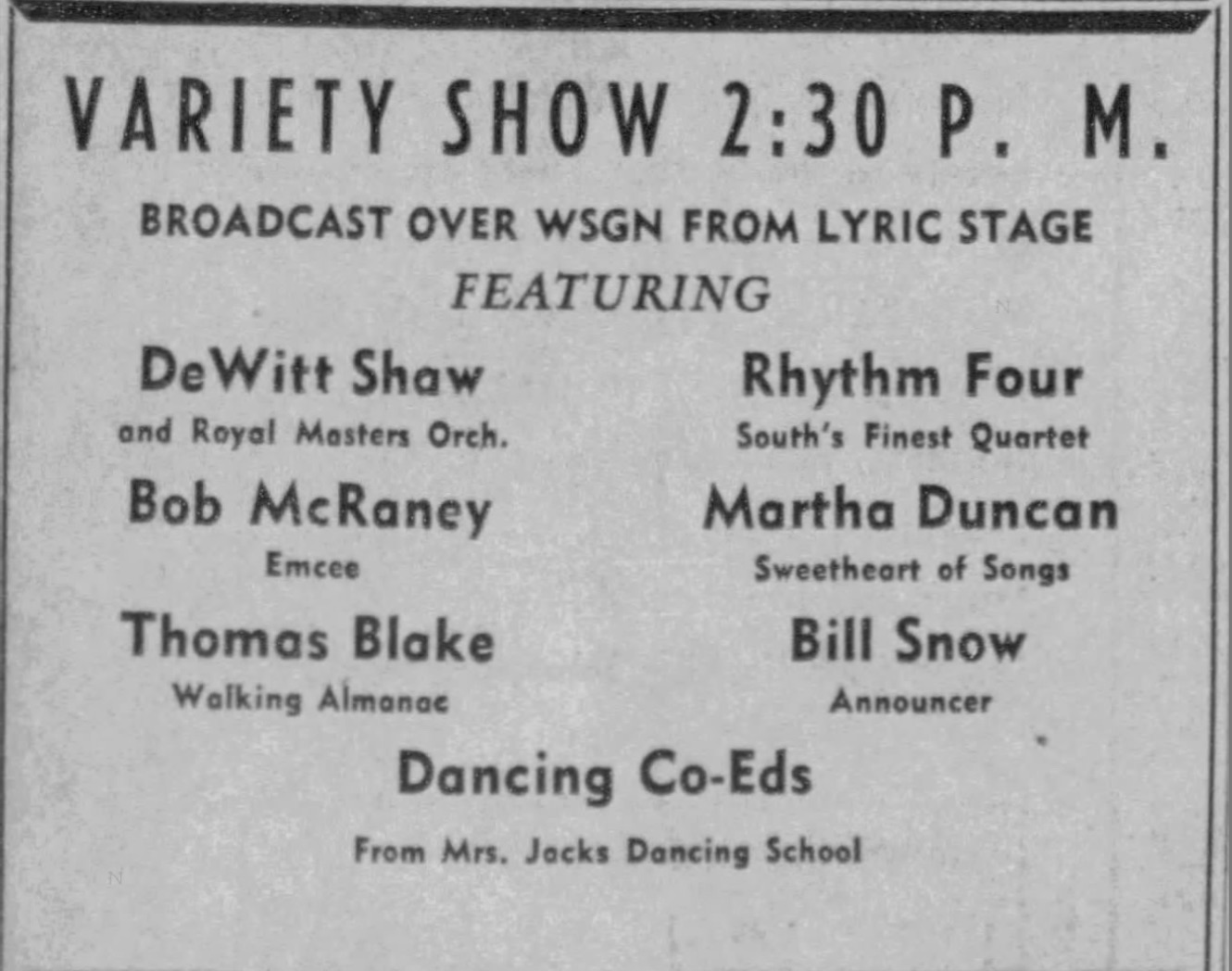

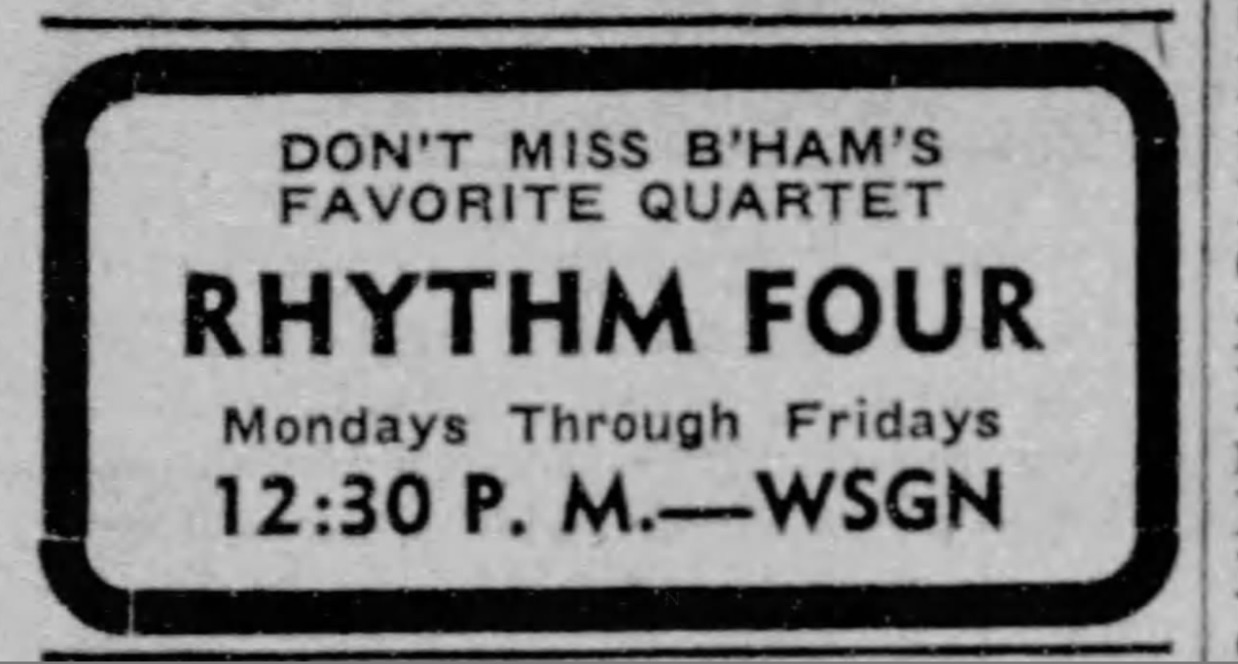

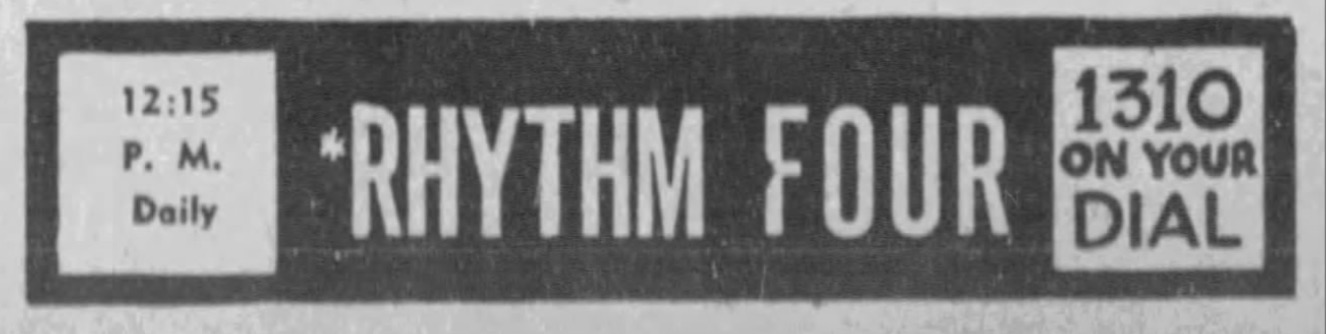

The quartet first appeared on the airwaves in the spring of 1939. On April 9th, an ad in the Birmingham News, the city’s leading white paper, announced that “Another outstanding local-live-talent program makes its debut over WSGN tomorrow…. The Rhythm Four, a Negro quartet, is one of the finest singing organizations in the South. Their blended harmonies are applied to currently popular ballads and Negro spirituals.” Another ad from the same paper, below, promises “Sparkling Rhythms!” and “Scintillating Harmonies!” in the group’s “distinctively-styled arrangements of popular ballads and folk songs.”

Sonny’s contributions were central to the sound and success of the quartet, and his involvement with the group was only one part of his active creative output. The Weekly Review identified Sonny as “a composer and arranger of no little talent,” adding that “When he’s not working with the Ripple Rhythm Four, Blount leads his own orchestra.” By October of 1940, when the photographs above were published, the Review already considered the Four “Birmingham’s favorite quartet”—a bold statement in a town flush with quartets, and a sentiment echoed in advertisements that appeared in the Birmingham News (below). The group’s recurring appearances in both black and white local papers suggests the reach of their appeal.

Some context: for decades, Birmingham was a hotbed of African American a cappella gospel quartets, a history that’s been chronicled in depth by Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff. The Rhythm Four, while more secular in its orientation, would have been unavoidably influenced by this distinctive homegrown tradition. In fact, bass singer and guitarist Clarence Driskell, pictured above, also belonged to a local gospel quartet, The Heavenly Four. According to Abbott and Seroff, singer Jimmy Ricks—“one of the most beloved figures in gospel quartet history”—had a brief tenure with the Rhythm Four as well, before moving to Detroit in 1941. After leaving Birmingham himself, Sonny settled for fifteen years in Chicago, where he legally changed his name to Le Sony’ra and, in addition to forming his own band, found regular work as a composer, arranger, manager, and producer for a variety of groups—including experimental vocal harmony acts like the Nu-Sounds and the Cosmic Rays. His work with the Rhythm Four would have inevitably informed those later efforts.

No known recordings exist, however, of the Birmingham quartet, and their photos raise several questions about the group’s repertoire and sound. The presence of two guitars, including a resophonic guitar, is intriguing: most Birmingham gospel quartets performed without instrumentation, and acoustic guitars are hardly associated with Sun Ra’s later work. A notice in the Birmingham News compares the Rhythm Four favorably to the nationally popular Ink Spots; the guitars and white dinner jackets reinforce that connection, hinting at the group’s possible sound. According to descriptions in the local press, Sonny’s piano (not pictured in the publicity shots, most likely for practical reasons) was a core feature of the group’s sound, along with the vocal harmonies and guitar accompaniment.

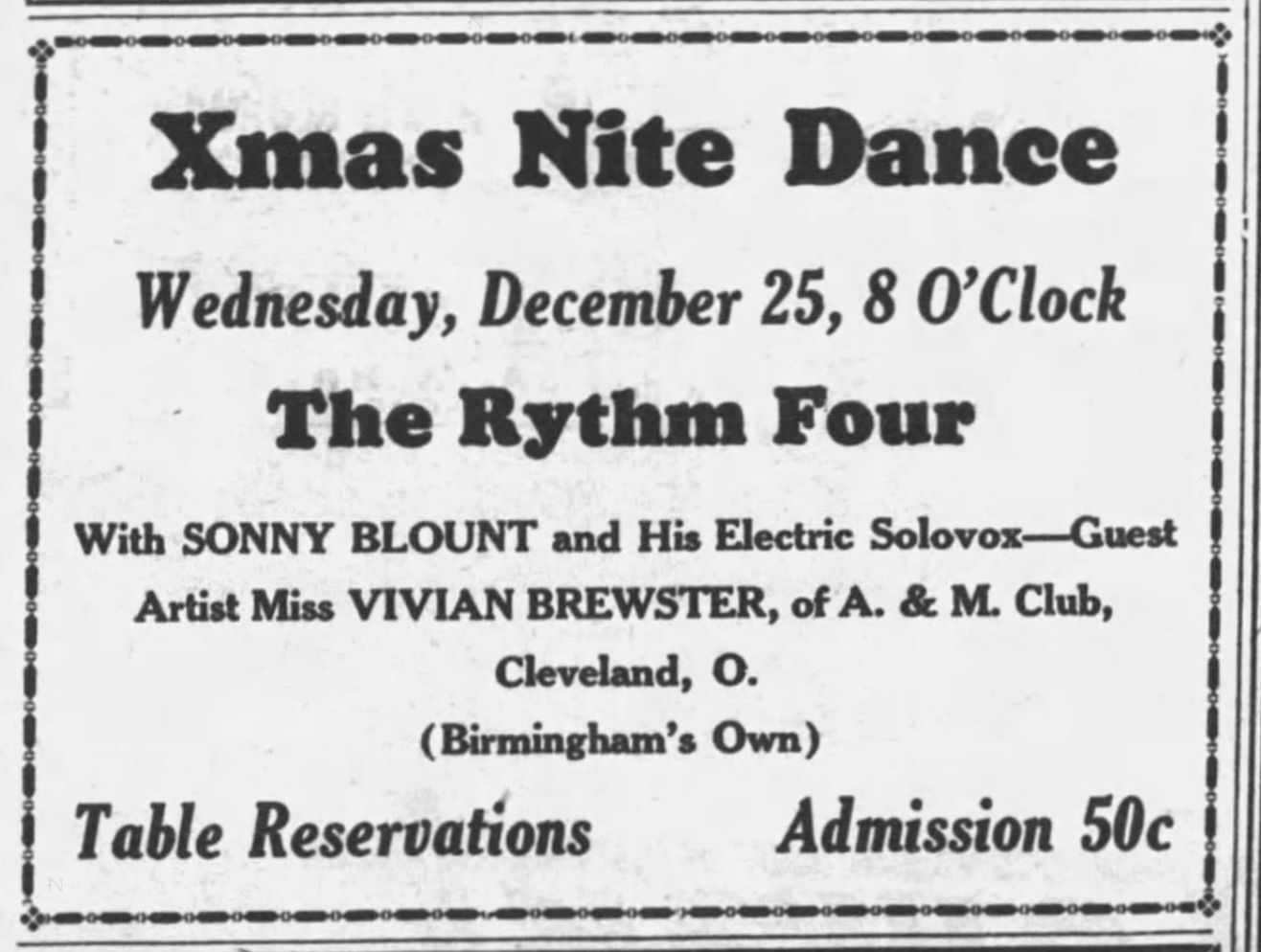

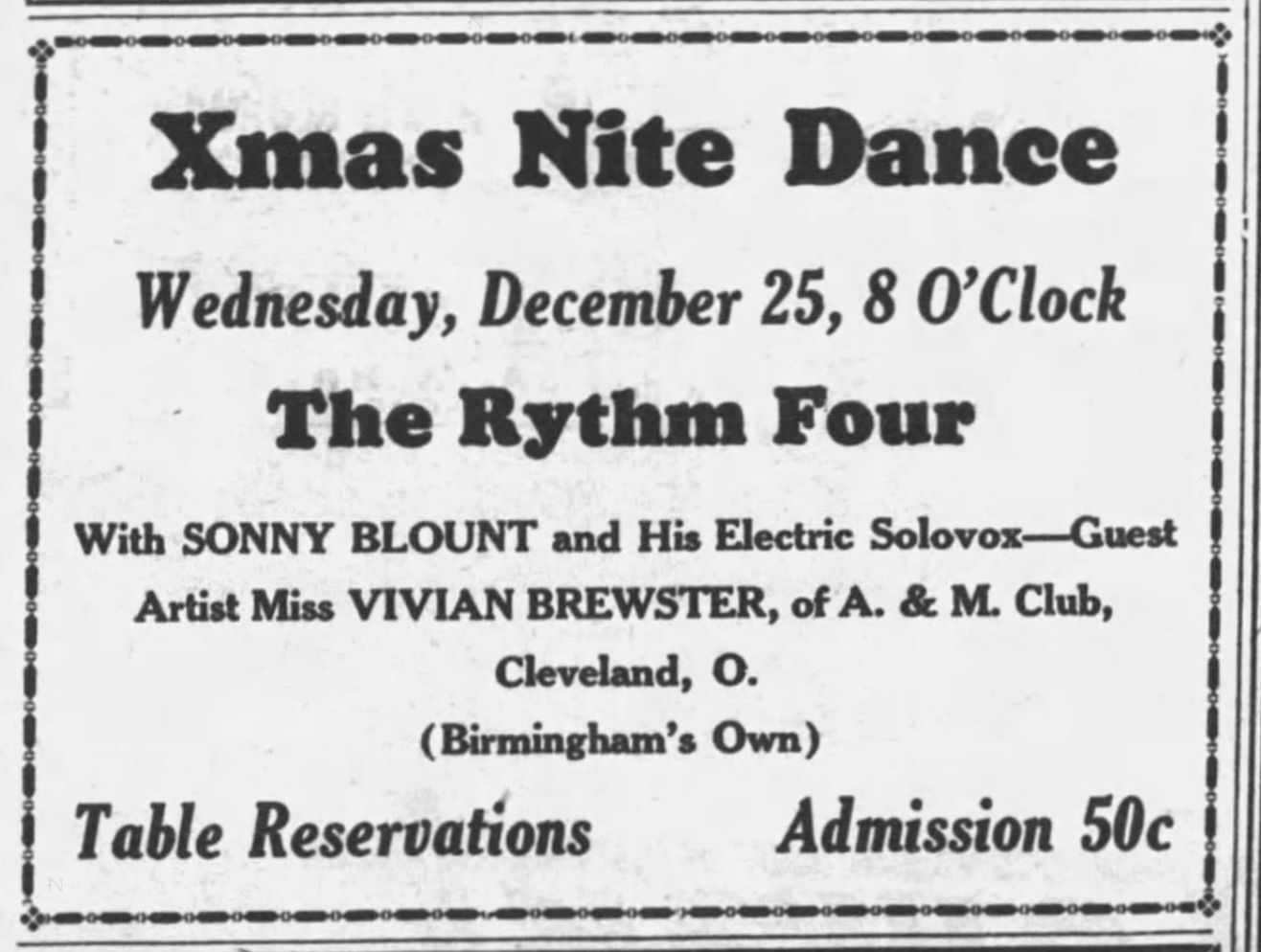

By Christmas of 1940, Sonny had added a new feature to the Rhythm Four’s sound. The Solovox, introduced earlier that year, was an electric attachment that added synthesized effects to an acoustic piano or organ. It became a trademark of all of Sonny’s Birmingham groups and reflects his early forays into new technologies. Years before synthesized sounds entered the mainstream of jazz—or of popular music, more broadly—Sonny Blount in Birmingham was experimenting with their potential, even in the quartet setting.

Clearly, this was no ordinary quartet.

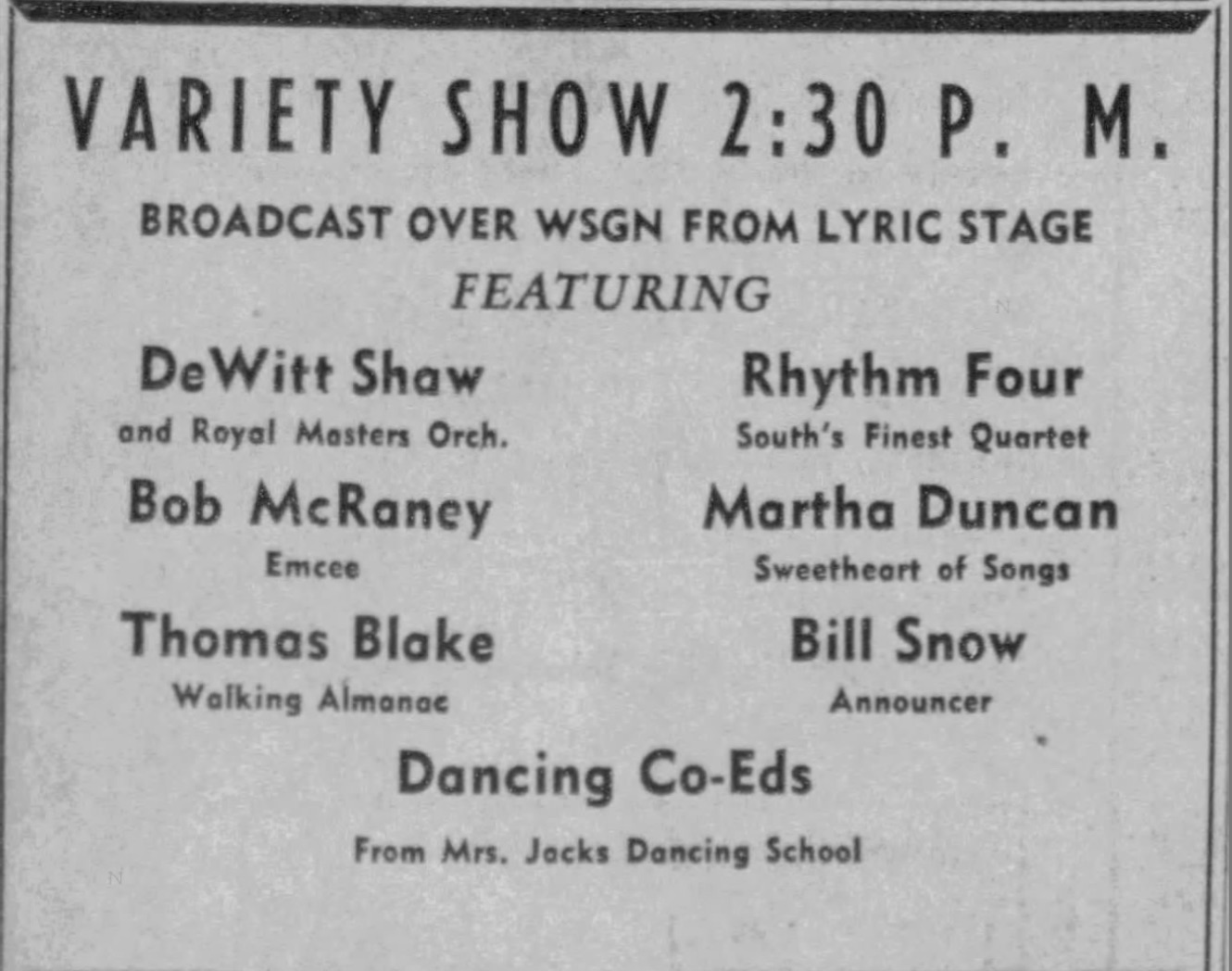

The Rhythm Four remained active in Birmingham through at least September of 1943. They were featured at a wide range of events, including society dances and charitable fundraisers in Birmingham’s black community. They performed for white audiences in variety shows at the Lyric and Alabama Theaters and in retail exhibitions at the Pizitz department store. All the while, their broadcasts over WSGN remained their steadiest gig, helping establish their reach in both the local black and white communities.

Here’s one more shot of the Rhythm Four, from July of 1943. If this is Sonny, he’d again be second from left—but this time, I’m not so sure it’s him. Turnover was not uncommon in groups like this, the resemblance here is less clear, and no names are mentioned in the caption. Despite Sonny’s key role in the quartet from at least 1939 to 1942, it’s possible that by now he’d moved on, his hands too full with his orchestra work. Then again, it might be him. Sooner or later, I hope to confirm this detail in one direction or the other.

Either way, it’s a compelling glimpse into Sonny’s world. And the headline—“They Do Jive Differently”—is fitting hint of things to come.

Part Two: Live Wire Entertainment — Swing Sensation Sonny Blount

For all its popularity, the Rhythm Four was never Sonny Blount’s primary focus. What mattered most, above all, was his band. And local ads reflect the movements of a bandleader on the rise.

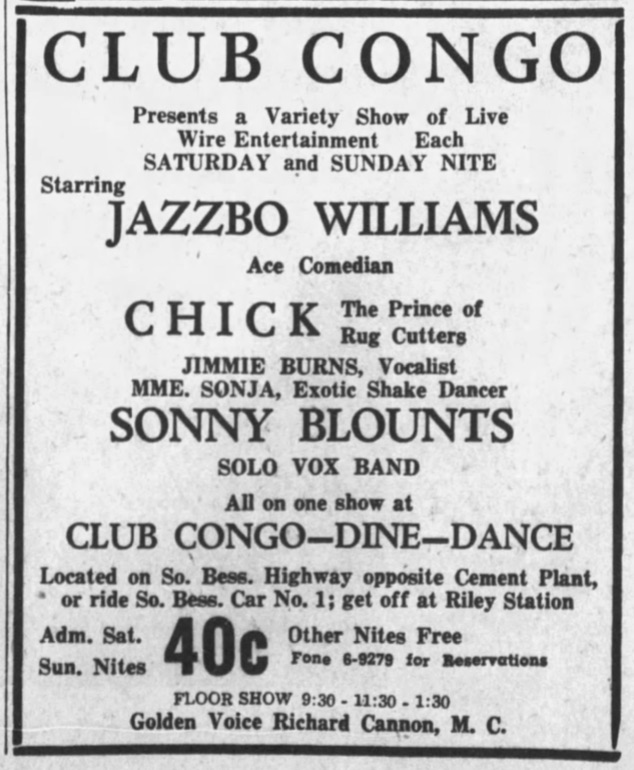

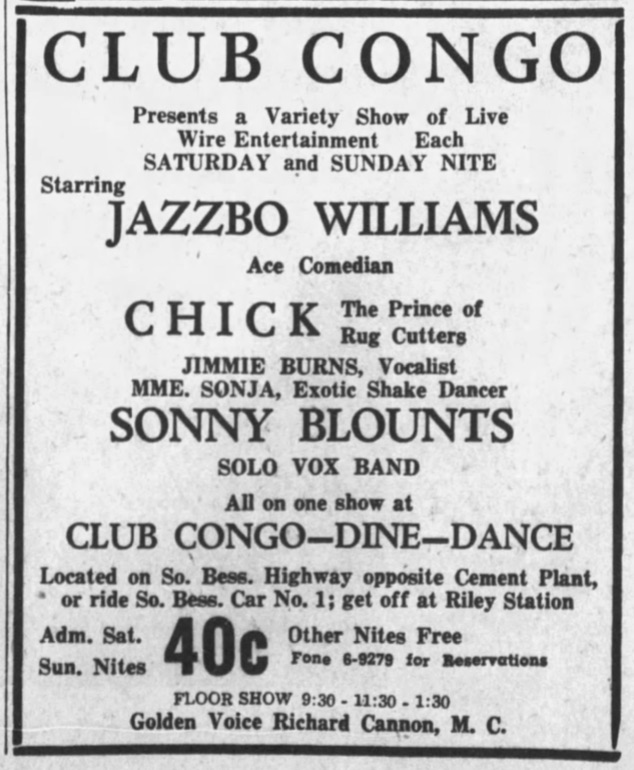

The Sun Ra of later years turned every live performance into a full-fledged spectacle, a musical happening replete with costumes, pageantry, dancing, parading, and audience interaction. In the early 1940s, Sonny’s standing gigs at Birmingham area nightclubs provided a kind of warm-up for those later events. Sonny was a popular regular performer at spots like Fourth Avenue’s “Colored” Masonic Temple and Eighth Avenue’s Elks Rest, where the most elite members of the local black community hosted lavish society dances. But at the Grand Terrace and Club Congo—two late-night clubs on the outskirts of town—his band could participate in spectacles more raucous. Night after night, Sonny Blount’s orchestra was central attraction in wild and wide-ranging line-ups that included not only musicians and singers but tap dancers, shake dancers, comedians, and female impersonators. An advertisement for Club Congo from July of 1942 promised “a Variety Show of Live Wire Entertainment Each SATURDAY and SUNDAY NITE.” Three times a night (at 9:30, 11:30, and 1:30) for 40 cents admission, Sonny Blount’s “Solo Vox Band” was joined by “Ace Comedian” Jazzbo Williams; Chick, “The Prince of Rug Cutters”; an “Exotic Shake Dancer” named Madame Sonja; and others.

A year later, Sonny was fronting similar line-ups at the Grand Terrace Café, located between Birmingham and Bessemer. Named for the famous Chicago ballroom, this Grand Terrace offered dining and dancing, a golf course and outdoor garden. Sonny Blount “and his New Rhythm Style Band” played Friday and Sunday nights in events whose casts included singer Fletcher “Hootie” Myatt (nicknamed for his signature performance of Jay McShann’s “Hootie Blues”); the shake-dancing “Madame Twannie”; Lillian Harris, a “Mammy Blues Singer”; and the “Fast Stepping Floorshow” of “Mess Around” Brown. Identified earlier as “Prince of Rug Cutters,” Chick—a staple of these shows—is identified now as a “famous female impersonator.” “Entertainers and band will play your request numbers,” the ads promise. On Sundays, dancing—prohibited during the day—commenced at midnight and continued until 2:30. Admission was fifty cents.

Recurring ads in the Weekly Review (see below, at right) included photos not of the entertainers themselves but of the Grand Terrace’s typical weekly crowds, urging readers to come out and join the scene.

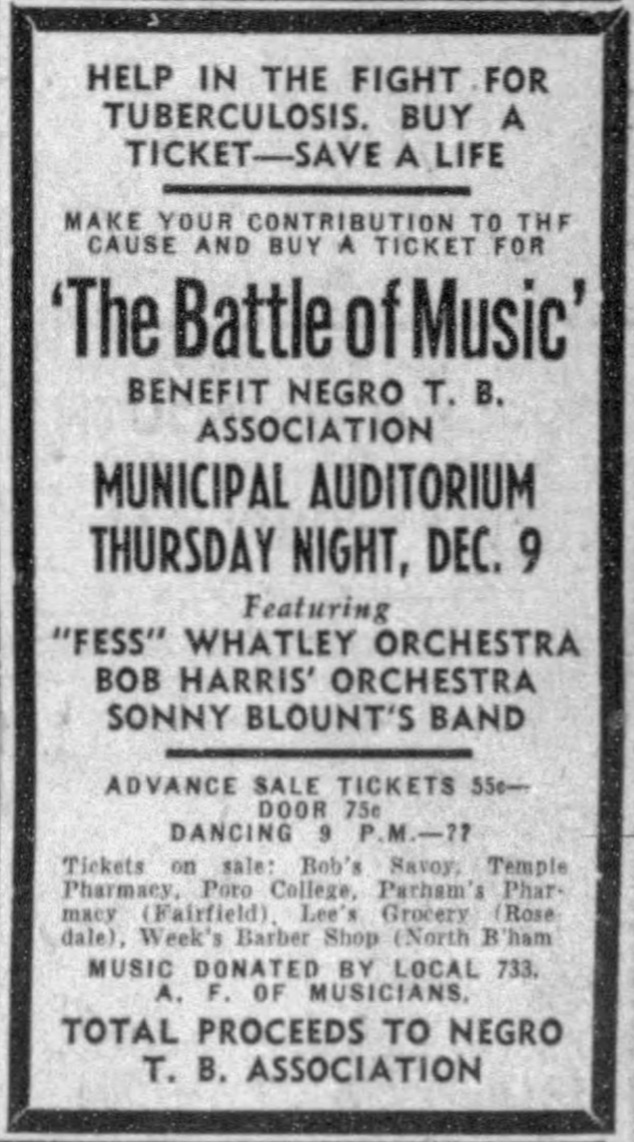

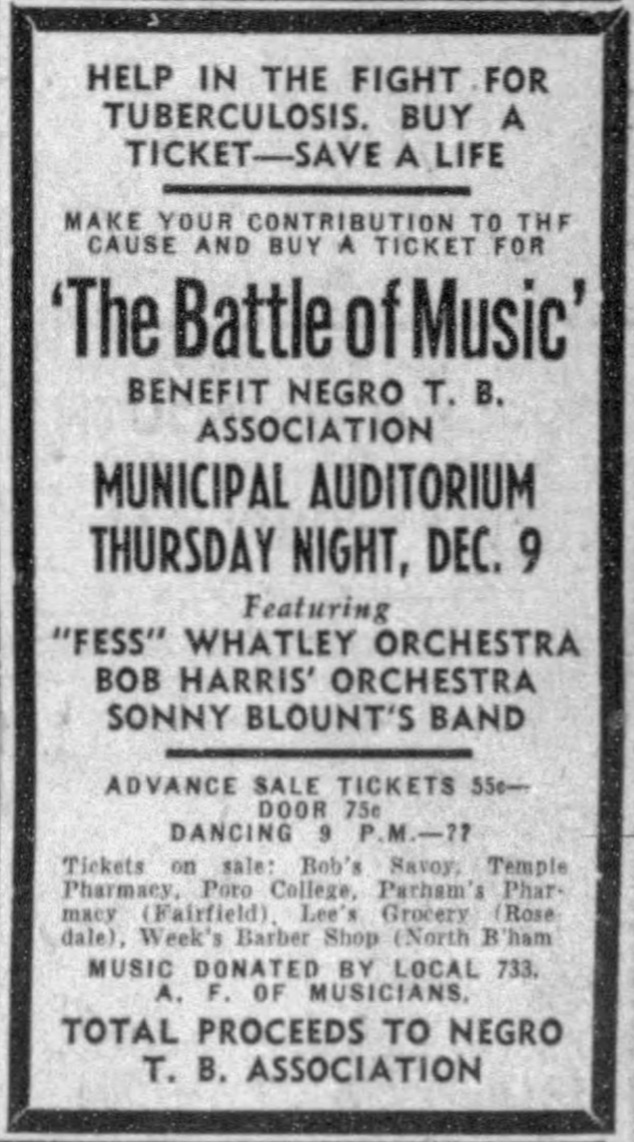

Sonny’s band also appeared at other popular events of the day, the much-hyped “Jazz Battles” — fierce if friendly cutting contests which pit one group against the next, each trying to outplay the other. Some contests, like the one advertised below, doubled as fundraisers for important local causes. Here (from December, 1943), Sonny and his high school mentor Fess Whatley faced off—along with a third band, the Bob Harris orchestra—in a benefit for the Negro T. B. Association. This “Battle of Music” was one of many events designed to combat the spread of tuberculosis in the black community.

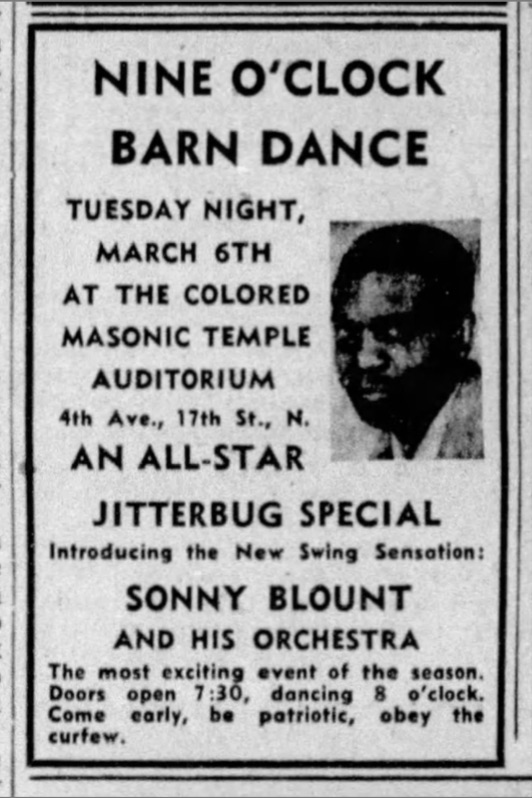

Finally, two advertisements from 1945—featuring one more early photo—reveal another kind of performance for the Sonny Blount band.

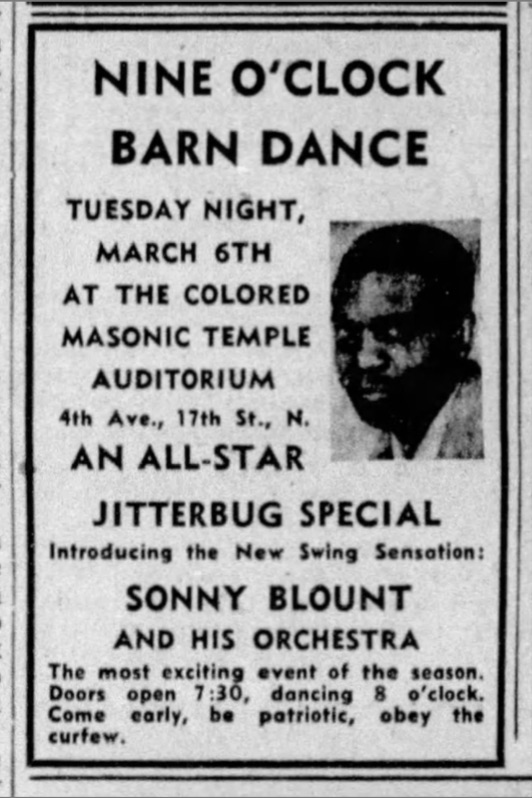

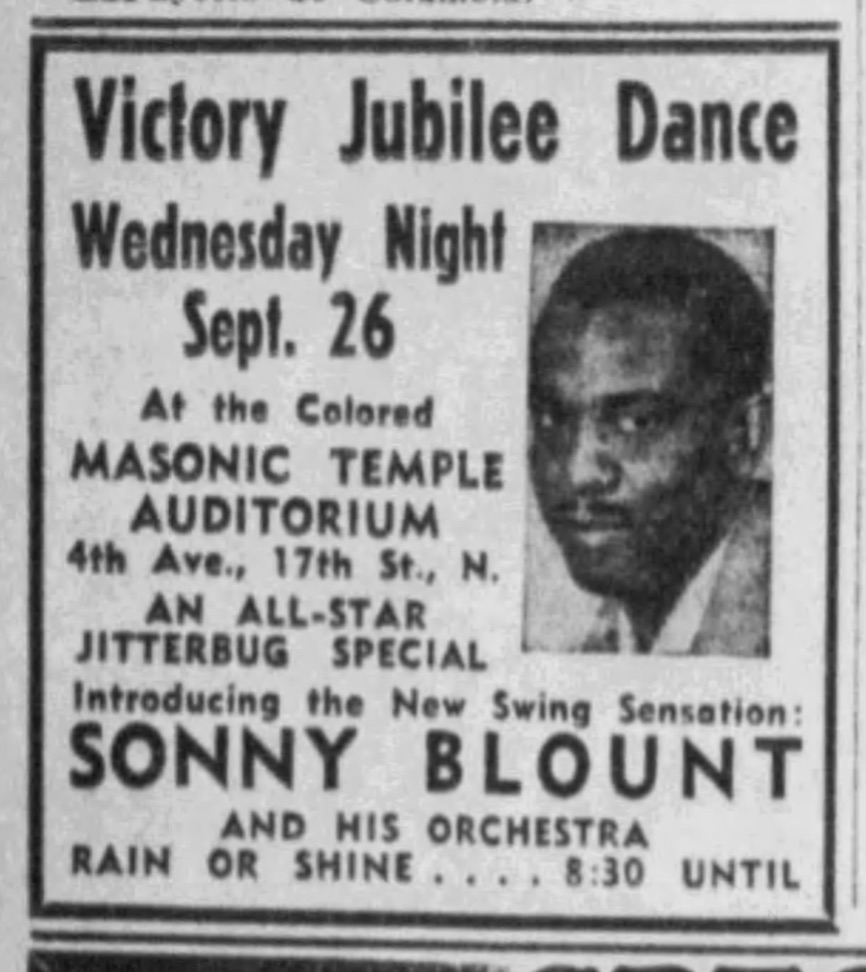

Fourth Avenue’s Masonic Temple was a central hub for Birmingham’s black social life in the age of Jim Crow. Its second-story ballroom hosted frequent appearances by local groups like Fess Whatley’s and Sonny Blount’s, and it brought to town major touring acts, including the Count Basie and Duke Ellington orchestras. Occasionally, the temple hosted special events for white audiences. This advertisement in The Birmingham News, from March of 1945, promotes such an event, a “Nine O’ Clock Barn Dance” and “Jitterbug Special Introducing the New Swing Sensation: Sonny Blount And His Orchestra.” Sonny had been well known for a decade already to black music lovers in Birmingham, and many white listeners would have heard his broadcasts with the Rhythm Four, even if they did not remember his name. Given the nature of segregation in Birmingham, Sonny likely remained a “new” phenomenon, indeed, to readers of the Birmingham News.

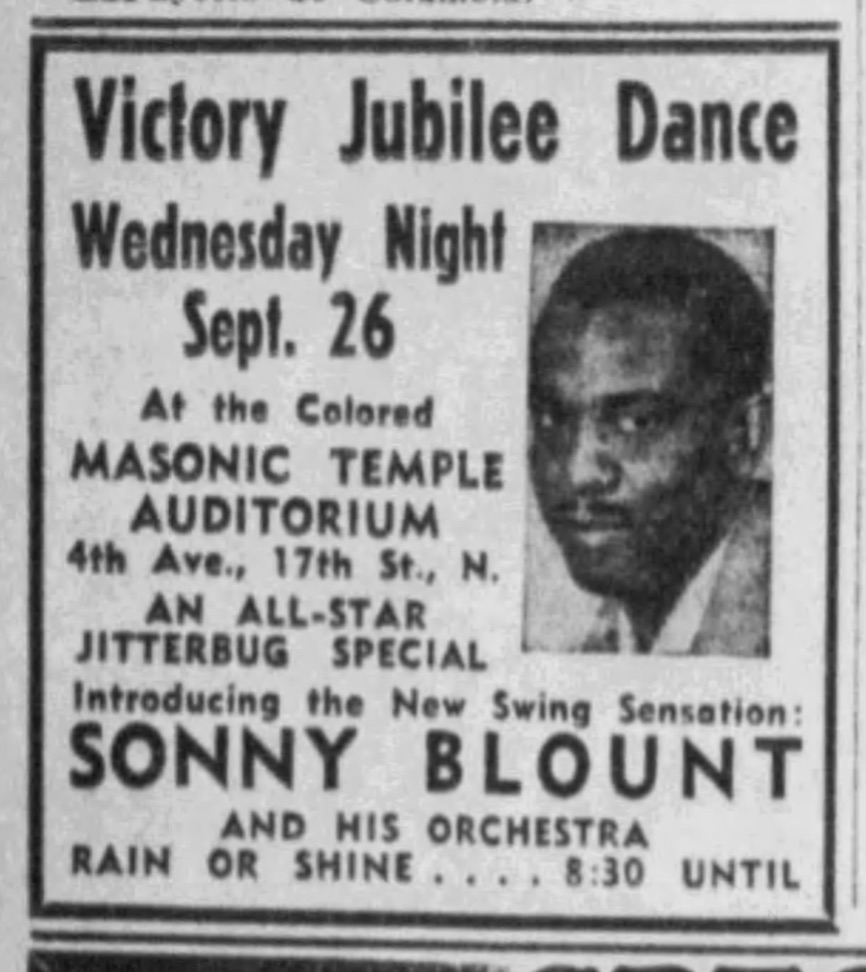

The above ad’s instructions—“Come early, be patriotic, obey the curfew”—refer to the wartime policy instituted nationwide that February, which demanded all entertainment venues close their doors at midnight. In September, the second world war came to a close, and the Masonic Temple invited white Birmingham revelers to another performance by Sonny Blount, this one billed as a “Victory Jubilee Dance.” This time, the event lasted “until.” The curfew had been lifted.

Readers of Space is the Place, John Szwed’s eye-opening Sun Ra biography, will remember the trauma and transformation the war years created for Sonny. That will have to be a story for another time — sorry! — but, suffice to say, Sonny’s feelings about patriotic victory dances must have been complicated. So were his feelings about Birmingham itself. Sonny left the city in January, 1946, a few months after that Victory Jubilee Dance.

He would create a new future for himself, and a new past.

*

Newspaper ads and write-ups offer invaluable hints about the past, but they only tell part of the story. For a more personal look at Sonny Blount’s Birmingham years, please check out my book, Doc: The Story of a Birmingham Jazz Man, an oral history of saxophonist and educator Frank “Doc” Adams, who played in Sonny’s band in the 1940s. In that book, in his own words, Doc Adams provides firsthand reflections of Sun Ra’s early days, helping fill in some blanks with intimate and visceral detail.

Earlier this month, I spoke about Sun Ra’s Birmingham years in a long interview with the Sun Ra Arkive. You can stream that conversation here for a deeper dive into Sun Ra history. Thanks to Christopher Eddy for hosting; I had a great time.

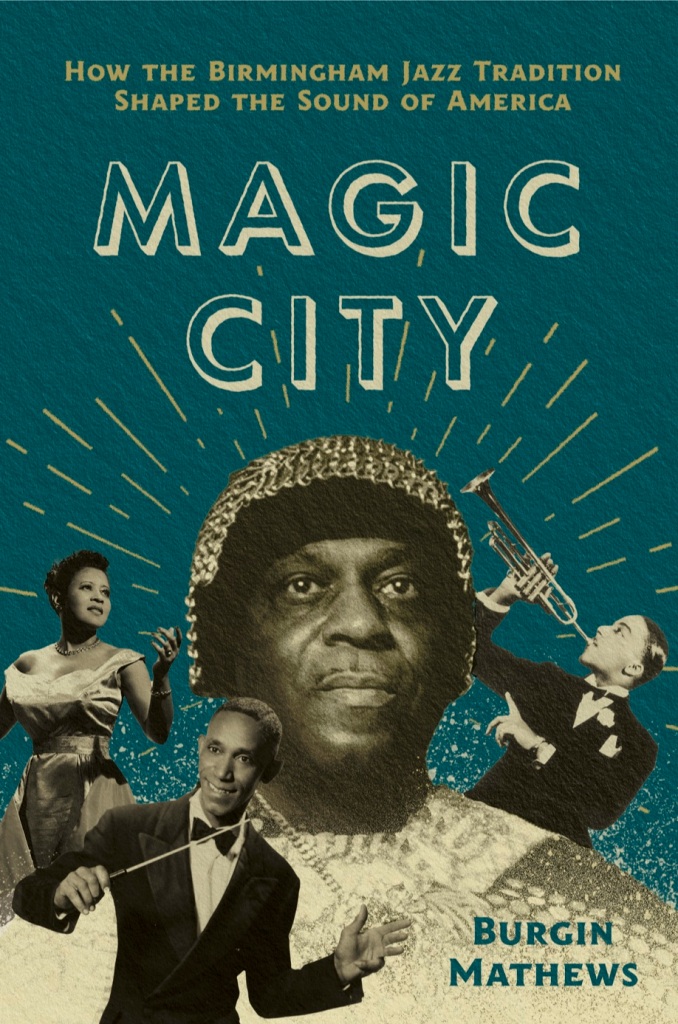

Meanwhile, I’m neck deep in wrapping up my second book, more than a decade in the making: a narrative history of Birmingham jazz, the culmination of all these years of researching and interviewing and writing and digging. It’s a great and important story, of which Sonny Blount is just one fascinating piece. You can follow this blog to stay in the loop—and you can support this next book by buying that last book (see above). Thanks.

Several posts on this blog have addressed Sonny Blount’s early years in Birmingham. You can scroll through all of them here. For further window’s into Sonny’s world, I recommend the stories about Sonny’s early bandleader, Ethel Harper, and about the popular Fourth Avenue venue Bob’s Savoy.

Two final notes: all Sun Ra researchers remain indebted to biographer John Swzed, whose groundbreaking Space is the Place was just reissued, a few weeks ago, with a new introduction by the author. That’s a great place to start if you want more on Sun Ra (including the story of his wartime clash with Uncle Sam). For Birmingham’s gospel quartet history, please see the extraordinary work of Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff—in particular their book To Do This, You Must Know How: Music Pedagogy in the Black Gospel Quartet Tradition.

(The book links above, by the way, are to bookshop.org, an excellent alternative to Amazon. Bookshop.org gives a significant chunk of its proceeds to independent, local bookstores across the country and even allows you to pick which favorite bookstores you want to support. Of course, you can get all these books through Amazon, too. Support working writers however you can—but whenever possible, please support local booksellers in the process.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.